We hear a lot about best practices. We talk a lot about them. Many organizations are of the opinion that if they can identify the best practice, they are set. Of course, that thinking can be limiting in a number of ways. We need to be better, not best.

Limiting Yourself with Best Practices

Googling “best practice definition” gives you “commercial or professional procedures that are accepted or prescribed as being correct or most effective.”

Wikipedia says : “A best practice is a method or technique that has consistently shown results superior to those achieved with other means, and that is used as a benchmark. In addition, a “best” practice can evolve to become better as improvements are discovered. Best practice is considered by some as a business buzzword, used to describe the process of developing and following a standard way of doing things that multiple organizations can use.”

Notice in the Wikipedia definition they add the idea that they can evolve to become better. This gets to the root of what we need to be doing.

Best practices can be useful for very straightforward tasks such as making dinner. Washing your hands is likely something most people can agree is a best practice before making a meal. There may also be specific steps that you want to take in preparing all meals — with some meals having their own best practices to get quality results. Here is where it gets muddy however. In the definitions we started with, they use ‘procedure’, ‘method’, ‘technique’, ‘standard’, and ‘benchmark.’ These can all have different meanings or at minimum, nuances to them.

Best practice is often used as a standard. Once we govern that standard with a policy and then a procedure, we impose a limit on our ability to be innovative and creative. We also tend to create complicated procedures to change other procedures — so there are added barriers and steps to even consider an improvement. We can try arguing that if someone has a “really good idea” and they are “not lazy” they will bring the idea up, but this thinking is naive at best. We have to create environments where the culture is focused on improvement. We lose so many ideas to improve and be even better.

The idea here is quite simple, if you are always aiming to simply align with best practices, you ARE stifling the innovation at your organization.

Best Practices Can Be Valuable

Best practices as a general concept certainly make sense. This is one reason the term is probably used so much.

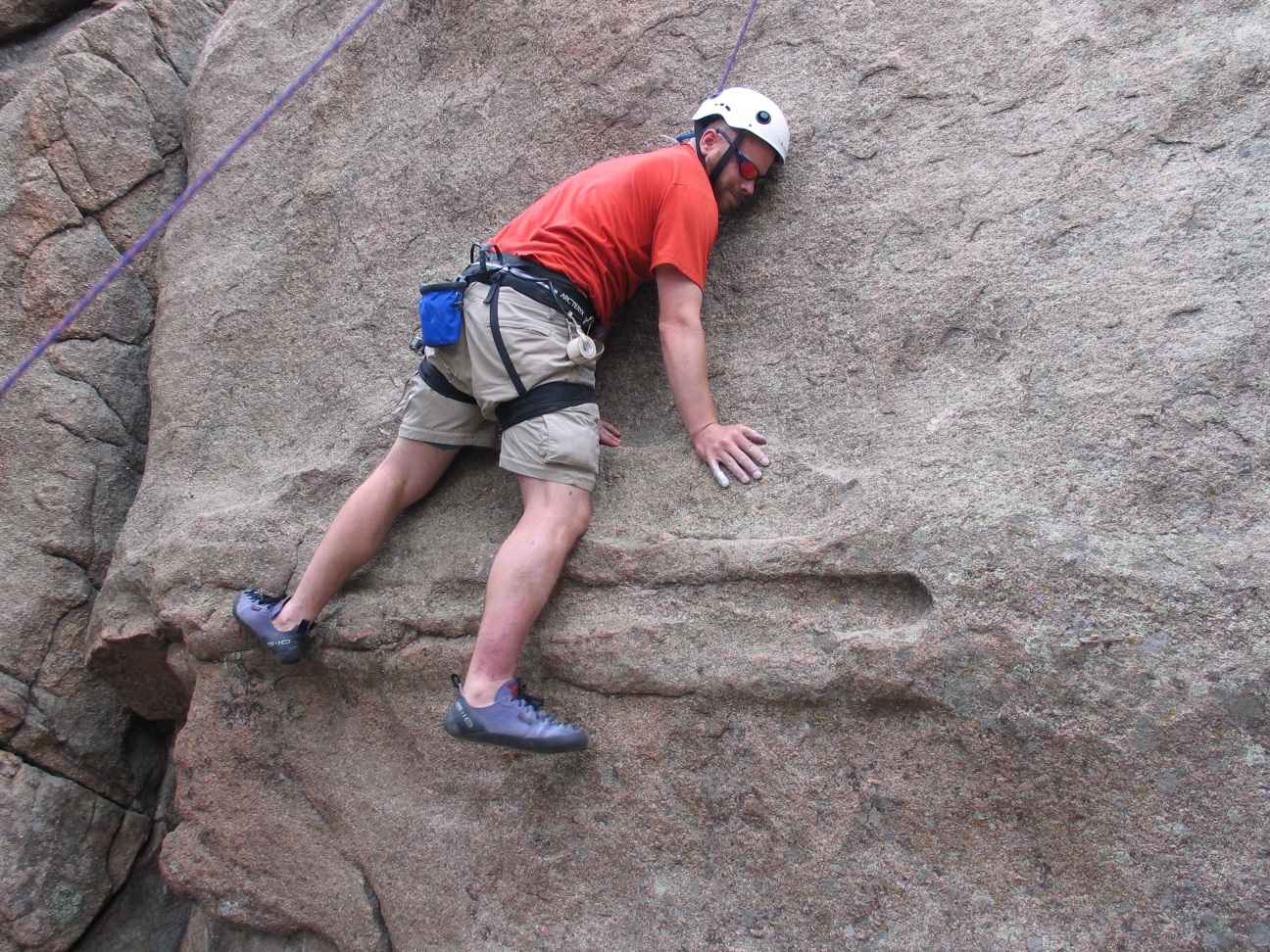

When you are rock climbing, there are a number of best practices. When you climbing and are tied into the rope, you say “On Belay?”, the person who is belaying you (stopping you from falling if you slip) says “Belay On.” You then say “Climbing” and they say “Climb On.” Some people don’t do the last “Climb On”, however I find it a useful step in the safety procedure. So that might be a variation. There are also other best practices, checking equipment, checking your partners climbing harness and knots, etc. These are not things I would compromise on. So we do have best practices, often associated with safety, that are smart and needed. These work in situations where we have very repeatable steps and processes. The question is, what happens when they do not work? What do people do? What if there was a blizzard with very strong wind. Could you hear the person say Belay On? What if you could not? What would you do if you were 75 feet away from them and could not see them? Suddenly this best practice does not work.

Best practices are valuable as a baseline for simple situations, but we overuse the term and do not clarify how they applied. We do not outline at what points it should be changed or where it might fail. We also have to contend with what we don’t know we don’t know. For people who have never rock climbed in conditions like I mention above, and who get caught in an unexpected storm, it never occurred to them to have a different best practice for that situation where they can’t see or hear their climbing partner. A best practice could give them a false sense of security, or worse.

Certainly we can forsee some of these events. We can learn from others, we can apply logic, we can attempt to consider what might happen. Many of us, including myself are quite good at seeing patterns and variations in patterns into the future. I had a boss many years ago, when I was starting out, who would call me “Radar” (from the TV show Mash). Radar was the guy who would show up without anyone requesting him with whatever was needed and finish people’s sentences. You always wondered how he knew what was needed.

That was valuable to me as an “expert”, but it can actually be a problem for me today, if I let it be. It can lead me to being “sure” I know what someone will do next. As we move from experts to levels of mastery beyond expert (expert is not the end of the journey) this thinking can be limiting. Of course being an expert can be a useful skill in many situations and we need experts throughout organizations. I consider myself to be an expert at hiking, but there are always limits. When I think about hiking in the mountains with my kids, I can think through a pile of possible scenarios and ensure we are prepared, to a point, for things to come. The basics are simple items like being ready for rain in case it rains — even though it is a sunny day. I know that in Colorado, rain is very likely every summer afternoon in the mountains — and storms come in quick. I also know that situations will come up that I will not expect and when safety is concerned, I need to plan for unexpected things. On a sunny day, do we need extra socks? Yes!

I was hiking with my son a few years back at about 10,000′ elevation. Rain started falling and we put our rain jackets and rain pants on. He noted that his toes were a little cold. We stopped under a tree and checked and his shoes had gotten wet inside. He had extra socks in his pack, so we put those on (and they were wool — cotton kills). The problem was his shoes were still wet inside. I was upset with myself for not buying him waterproof shoes. Being upset did not solve the problem, nor did shaming myself. I looked at what we did have in our packs. We always carry a few 55 gallon garbage bags in our packs (among other things!). These can be used for more or less anything (poncho, to sit in, a shelter, etc.). I was going to cut one up with a knife and make shoe liners for them (a trick I recall from my mom that we used as kids to keep our feet dry when we were spending hours in the snow playing or when our boots were not keeping the water out) — then I realized, I could actually re purpose the snack bags we had. This would save the other larger bags in case the rain got harder or it started to snow (can happen at high elevations even in the summer) and we needed an emergency layer. So that is what we did. They were a bit tight and of course did not breathe (which might cause his feet to get wet or blister — but in the short term — not an issue), but his feet warmed up.

What do you make of this story? The best practice might have been waterproof shoes — coulda-shoulda-woulda — that is not what we had. Even if we had waterproof shoes, guess what – all shoes have a hole where your foot goes in — they can still get wet inside or be cold. We can also apply best practices that allow us more options. One standard I use when packing for a longer hike, is to assume we will have to sleep outside that night. You might twist an ankle or someone else in your group might. I find this standard helps me be prepared for the unexpected, which happens a lot, even after years of camping, backpacking, hiking, climbing, trail running, and even spelunking once. How ridged is your standard? Does it create or limit options? Most tend to limit options. Can you adapt your plan and ideas? Can you innovate and be creative?

So while there is some value to best practices in certain situations, to assume you have all the answers in an increasingly complex and high-speed world is a giant assumption with many risks.

Assessing Best Practices

When we look at our organizations, this question of “can we be creative and innovative?” is a critical one.

What best practices do you have in place that are limiting your success?

You may have best practices that are failing already. If you can see them failing, that is great — if you take action. What about when you can’t see them failing?

Four straightforward tactics to start assessing your best practices:

- Start by simply listening. What are you hearing. Listen for the words I mentioned above (best

Look to better practices instead of settling for best practices! practice, procedure, method, technique, standard, and benchmark). How are they being used? Do you hear things like “We have to do it that way to comply with the standard.”?

- Look for words that prevent innovation. The words above are part of those since people can use “standard” or “best practice” to stick to a process that is comfortable. There are however a number of other words that are used a lot in a way that inadvertently prevents change. A few of these words are: legal, quality, audit, human “resources”, and even “the customer said.” These are words that get used like “the legal department said” or “the quality department said” (as in a quality department at an organization that makes medical devices and is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (in the US)). An example that comes to mind is a time I was working with a team in a release planning meeting. The team noted that they “had to complete a diagram for audit as part of the development process and that would add a lot more time to the work.” They way they said it, it led me to ask how they used the diagram. They said they did not. . . and went on to say that audit did not either. Through more questions and discussion, I learned that they can changed the process since the audit finding (a year or more back) and this diagram was literally of no use. No one even looked at it. The next thing that happened proved the point. They went back to talking about how they could not get all of the work done in a sprint, given the diagram requirement from audit. The simple fact that “audit” requested it was enough to override the fact that everyone knew it was useful. It could not be questioned. They could not even think about it as an option to question. We grabbed the VP who was in release planning and explained the situation to him. His response was “Don’t do it, I’ll take care of it”, which is what we needed. This issue went beyond the teams ability to address it themselves. Ask yourself what words are preventing you or your organization from innovating, being creative, or simply maximizing the value delivered to customers? It is also important to note that these were smart people. If you are tempted to say “my teams or organization would not do that”, you are kidding yourself and making a dangerous assumption.

- Ask questions that focus on what else is possible or could be different. You might ask “What if we did it another way – what might that look like?” or “what would happen if we spoke with audit?” or “what would you do if you were in charge for a day?” There are many more questions like this. The key is to ask questions that focus on what might be possible.

- Focus on moving to Better. As you identify best practices that may not be performing the way they were intended, facilitate sessions to identify ways that these can be improved or replaced. Look at what you can put in place specifically to focus on continuous improvement. These sessions can be run in many ways with many formats (retrospective formats, impact mapping, root cause analysis, etc.).

Be Better, Not Best

Remember that best practices are not always the answer. They can add value, if you understand the types of best practices you have. When they are used as blankets to cover innovation (reminds me of agile area rugs) they are not useful. If we want to foster a culture of continuous improvement, we have to zero-in and address pockets that prevent us from getting better. Best practices is often one of those places. Don’t get stuck and limit yourself to best, move beyond that to better. Best practices or even great practices should not stop you from getting better!