You’re a mid-level manager in a rapidly growing company. Your boss tells you that a new initiative the company has been considering for the last year has finally gotten the go-ahead from the executive team. This initiative is similar to others your company has taken on in the previous few years, but it is different in a few key ways. There’s no playbook for work like this; success will require trying new things and learning from what happens. Your job is to pull together a team that will perform at a high level in challenging circumstances. What do you do?

Teams

Leadership Isn’t About You

Managers everywhere struggle to lead teams. These teams don’t produce the desired results, leaving everyone frustrated. A common cause of this problem is managers falling into the trap of thinking that leadership is about them. When this happens, a change in perspective can help them regain effectiveness.

Monitoring Three Processes to Help Team Performance

A high-performing team meets or exceeds its clients’ expectations, becomes more effective over time, and helps all members learn and grow. A high-performing team is not merely highly productive; it is anti-fragile. Teams reach high performance through a complex process of development. How can you tell if it is moving along that path or needs a corrective nudge? By monitoring three key team processes.

Conditions for High-Performing Teams, Part 2

Why do some teams perform at a high level while others struggle? To be clear, when I talk about a high-performing team, I mean one that is highly productive, continues to improve over time, and develops all of the people who are part of it. Teams are complex systems, so you cannot directly cause a team to perform at a high level or predict with certainty that it will or won’t. You can, however, create conditions that make it more likely a team will develop in the way you hope.

Conditions for High-Performing Teams, Part 1

Team performance is an emergent phenomenon. You can’t control it, and attempting to adjust it directly will likely have perverse effects and unintended consequences. As with any complex system, your best option for influencing it is by managing constraints. Instead of thinking about “What do I do to create high-performing teams?” shift to considering, “How do I foster the conditions in which teams are more likely to become high performing?”

What is a High-Performing Team?

“Oh, my teams are definitely high-performing.” I’ve heard this from countless managers in numerous organizations. Sometimes I wondered where they were keeping all the low-performing teams. Understandably, managers responsible for developing teams want to be seen as doing a good job. Isn’t the promise of high performance the reason we form teams? Without a clear definition of what “high performance” means, it’s easy to defend describing many teams with that term. And if a team is already high-performing, they don’t need to get better, right?

“Oh, my teams are definitely high-performing.” I’ve heard this from countless managers in numerous organizations. Sometimes I wondered where they were keeping all the low-performing teams. Understandably, managers responsible for developing teams want to be seen as doing a good job. Isn’t the promise of high performance the reason we form teams? Without a clear definition of what “high performance” means, it’s easy to defend describing many teams with that term. And if a team is already high-performing, they don’t need to get better, right?

Not All “Teams” are Real Teams

Few words in the corporate world are abused and misused more than “team.” All the people who report to the same manager? They must be a team – even though their work doesn’t require them to collaborate. All the people working on a product? They must be a team – even though they all have different objectives and incentives. Most “teams” are collections of people that someone has drawn a somewhat arbitrary line around and said, “You’re a team.” Calling something a team doesn’t make it one. Teams have three essential qualities that set them apart from other collections of people.

What Customer Problem Are You Trying to Solve? (And Why?)

Many product teams fall into the trap of fixating on the work they need to do and forgetting about the impact their work is supposed to have. When that happens, the work often doesn’t produce the desired result. When you work as part of a product team, five questions can help you to avoid this trap by re-focusing on the customer problem you are trying to solve – and why.

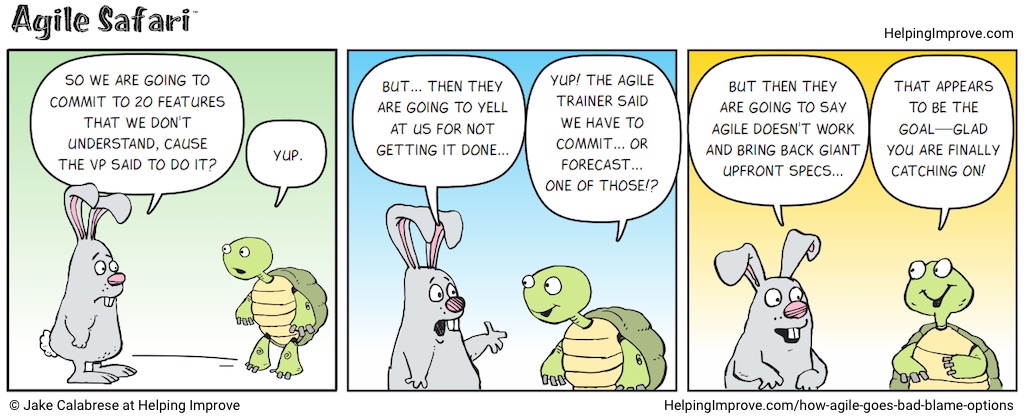

Agile Leadership Myth #2: Self-Organizing Teams Don’t Need Help.

Self-organizing teams do need help. Self-organizing teams are not instant, automatic, or magically created, despite what is often implied. There is a process to become this type of team, and it is rarely, if ever, a straight line. The help they need differs from more traditional directive assignments and task management.

To unravel this myth, we must look at what self-organizing means, what teams and managers experience, and what you can do to shift your help to a more ROI-friendly approach!