Teams rarely have a shortage of complaints. Most teams have plenty of ideas of what’s going wrong and numerous suggestions for addressing them. Noticing what’s getting in the way of great work is a sign of a healthy team. However, they often focus too much on what others can do to remove these obstacles. When teams ignore what they can do themselves, things rarely get better. One of my favorite tools for empowering teams is Circles & Soup.

Teams rarely have a shortage of complaints. Most teams have plenty of ideas of what’s going wrong and numerous suggestions for addressing them. Noticing what’s getting in the way of great work is a sign of a healthy team. However, they often focus too much on what others can do to remove these obstacles. When teams ignore what they can do themselves, things rarely get better. One of my favorite tools for empowering teams is Circles & Soup.

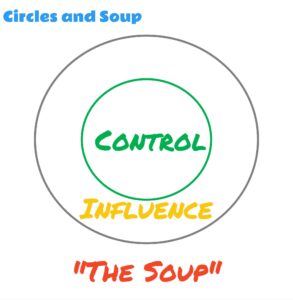

Understanding Control, Influence, and “The Soup”

Circles & Soup is a tool I learned from Diana Larsen. It’s a variation of Steven Covey’s “Circles of Influence and Concern” from The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. It helps people sift and sort through ideas for action, and it’s one of my most frequently shared and used tools. It’s a simple drawing of two concentric circles, which divides the diagram into three regions. The area inside the inner circle is labeled “Control.” The region outside that circle but inside the other one is labeled “Influence.” Finally, the space outside both circles is labeled “The Soup.”[1]

Circles & Soup is a tool I learned from Diana Larsen. It’s a variation of Steven Covey’s “Circles of Influence and Concern” from The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. It helps people sift and sort through ideas for action, and it’s one of my most frequently shared and used tools. It’s a simple drawing of two concentric circles, which divides the diagram into three regions. The area inside the inner circle is labeled “Control.” The region outside that circle but inside the other one is labeled “Influence.” Finally, the space outside both circles is labeled “The Soup.”[1]

I use this tool with a team when I notice most of their complaints or suggestions involve things outside their control. I wait until they’ve come up with ideas addressing their complaints, which they usually write on sticky notes. Then, I draw the diagram and ask them to sort their ideas into three broad categories. I explain the categories with three personal examples.

What goes into the Circle of Control are things that you have the authority to decide, like when you choose to get up in the morning. If you want to get up earlier, you don’t need anyone else’s permission (though you might want to let certain people know). You can take direct action, which in this case means setting your alarm for the new time and getting up when it goes off.

What goes into the Circle of Influence are those things you can’t decide unilaterally but need to influence others to make happen. Something in your Circle of Influence is going to lunch with friends or co-workers. You can suggest or recommend when and where you might go together, but you don’t control the decision. You can take persuading or influencing action, but ultimately, you need their buy-in to have lunch with them.

Finally, what goes into The Soup are things you have neither control nor influence over. For example, you can’t control or influence the weather – at least not in the short term. You can decide what to do when the weather does something undesirable. If it rains, you can wear a jacket or grab an umbrella. You can choose to stay inside. You can decide to go somewhere else that has different weather. Or you could go outside in the rain and splash in the puddles. In the Soup, you choose how you respond when unexpected (or unwanted) events occur.

Finding the Soup

Once I’ve gone through these examples, I ask the team to sort their ideas based on whether or not the team has control, influence, or neither over the suggested action. Inside the Circle of Control go those things the team can do without anyone else’s approval or permission. Inside the Circle of Influence go those things where someone outside the team has the authority to make the necessary decisions. And in the Soup are the things that are beyond that.

Once I’ve gone through these examples, I ask the team to sort their ideas based on whether or not the team has control, influence, or neither over the suggested action. Inside the Circle of Control go those things the team can do without anyone else’s approval or permission. Inside the Circle of Influence go those things where someone outside the team has the authority to make the necessary decisions. And in the Soup are the things that are beyond that.

This level of explanation is enough to get a team started. The only difficulty I usually see is when two team members disagree over where a particular sticky note should go. This disagreement isn’t a problem; it’s a sign that they have different ideas of what tackling the issue would involve. They might have the same problem in mind but are considering two different actions to address it. In this case, a good approach is splitting the idea into two sticky notes and placing each separately.

Avoiding the Lure of the Soup

Why is the region outside the two circles called the Soup? As Diana Larsen describes it:

I borrowed the useful concept of “The Soup” from David Schmalz, all those elements of organizational climate & culture, policies & procedures, and other systemic factors in organizations that have become so embedded in “the way we do things around here” that the team has little hope of shifting them without considerable help and political will on someone’s part.

For things in the Soup, it’s unclear if anyone has the decision-making authority to change things. Even if there is someone, a decision isn’t likely to change things. Things are too entangled and too messy to address directly. A good rule of thumb is that if your boss’ boss can’t do anything about it, it’s in the Soup.

For things in the Soup, it’s unclear if anyone has the decision-making authority to change things. Even if there is someone, a decision isn’t likely to change things. Things are too entangled and too messy to address directly. A good rule of thumb is that if your boss’ boss can’t do anything about it, it’s in the Soup.

The first time a team uses this tool, I expect that more than half the things they want to change are in the Soup. This fixation is normal. We feel the effects of things in the Soup despite our inability to influence them. We may often complain about these things precisely because we can’t change them. Covey called this the Circle of Concern because we tend to worry a lot about things we can’t influence. The gap between what we can influence and what we are concerned about causes us angst. Covey’s point was that at the personal level, you have two options for dealing with this: Increase the amount of influence you have, or reduce the number of things you worry about – or both.

Taking Appropriate Action

With Circles & Soup, teams can take action in each of the three regions. The key is realizing that in each category, they need to take a different kind of action. Sorting helps the team identify how they need to address the problem.

Inside the Circle of Control, the team needs to decide and act. The center is the realm of direct action. They may need to let people outside the team know what they are doing, but the choice is theirs. Activities that fall here are what I call “high-percentage choices.”

Inside the Circle of Control, the team needs to decide and act. The center is the realm of direct action. They may need to let people outside the team know what they are doing, but the choice is theirs. Activities that fall here are what I call “high-percentage choices.”

For example, a software product development team might complain that they’re spending a lot of time waiting for the team’s UX researcher to write up the results from their discovery and usability tests with customers. While this documentation is supposed to help the software engineers on the team know what the customer expects the software to do, the engineers frequently misinterpret it. A way of addressing this problem that falls within the team’s Circle of Control is to have the engineers sit in on the usability tests with the UX researcher. When debriefing after the testing, they can decide what to write down and what just to do. Making this change to their process is entirely within the team’s authority; they don’t need anyone else’s permission to start doing it.

Inside the Circle of Influence are suggestions the team can recommend to others but can’t just do. They may be in someone else’s Circle of Control, but not this team’s. This is the area of recommending or influencing action. Here, the team must identify who they need to influence, what they want them to do, and why doing that matters to them.

Inside the Circle of Influence are suggestions the team can recommend to others but can’t just do. They may be in someone else’s Circle of Control, but not this team’s. This is the area of recommending or influencing action. Here, the team must identify who they need to influence, what they want them to do, and why doing that matters to them.

For example, a Learning and Development (L&D) group might complain that the training classes they deliver for managers of various departments aren’t addressing the managers’ problems. Requests for training come through the HR Business Partners (HRBPs). Because they aren’t familiar with the group’s new offerings, the HRBPs are not matching managers’ needs with the appropriate training. The L&D group wants to move from an “order-taker” role to a partnership with HRBPs. They can offer to join the HRBPs for intake sessions with managers. They can point out that working together like this will improve the department managers’ evaluations of their HRBPs (and the L&D group) through improved service. This idea is something that they can recommend but not insist on. Because the decision ultimately lies with people outside the L&D group, this idea falls in their Circle of Influence.

Out in the Soup is the area of responsive action. Problems that emerge from the Soup effectively can’t be changed. There are two things teams can do about an issue they have identified in the Soup. The first to plan countermeasures. When the thing they don’t want to have happen does, how will they handle it? What can they do to reduce its impact? Second, they can create transparency while accepting that things may not change. The key is for is transparency not to sound like whining. Teams need to point out problems as neutrally as possible. They need to focus on the impact it’s having in terms that their audience cares about.

For example, a marketing team might have struggled to establish consistent practices and build its members’ skills. Right when they feel like they have a handle on things, the head of their division announces an aggressive hiring plan that will double the size of the group in the coming year. The team complains that this “hockey stick” growth will likely put them back into the chaos they’ve just spent the last year getting themselves out of. They are unlikely to be able to put this growth on hold; it’s connected to a larger business initiative.

Instead of allowing inconsistency to emerge in their practices, the team can take a different approach. They can track the lead time and throughput of creating marketing collateral and the time they spend on interviewing, hiring, and onboarding new team members. They can be proactive about forecasting to the division head how they expect their lead time to increase and their throughput to drop as they focus on integrating the new team members. When questions arise about why things are taking longer, even though the team has grown, they can point to the amount of time they’re spending on training and onboarding and how the level of quality of their collateral has not dropped. This transparency creates an opportunity to talk about the short-term tradeoffs versus long-term benefits of the hiring plan.

Moving Toward the Center

Several years ago, I led an offsite for a group of senior managers who complained that their teams’ retrospectives generated a lot of complaints but rarely led to concrete improvements. I shared Circles & Soup with them and asked where the ideas for action tended to land. Unsurprisingly, the teams focused on the Soup. The managers realized that not only did their teams tend to obsess about things they couldn’t control or influence, but they did, too. The teams were mirroring their managers’ patterns of ignoring the things within their control. I remember one manager’s takeaway from the offsite: “I need to stop trying to control the Soup.”

Getting a team to focus on what they can control is empowering. Introducing Circles & Soup allows you to nudge them closer to the center. Focusing on what they can control is one of the simplest ways to increase their sense of efficacy. When teams learn to recognize the Soup, they stop trying to control it and start doing things that matter instead.

[1] In Leading Amazing Teams, we use another variation: Circles of Control, Influence, and Concern.