Some of my most spectacular failures working with teams have come from going deeper than I needed to. One particularly memorable retrospective ended with a product manager declaring, “I’m done talking about my feelings.” (It was not my finest moment.) Yes, organizations are made of people. And yes, work happens inside a container of relationships. But that doesn’t mean every attempt to address a team or organizational problem must be super deep. Choosing the depth at which to intervene is critical for every manager, consultant, and coach.

Some of my most spectacular failures working with teams have come from going deeper than I needed to. One particularly memorable retrospective ended with a product manager declaring, “I’m done talking about my feelings.” (It was not my finest moment.) Yes, organizations are made of people. And yes, work happens inside a container of relationships. But that doesn’t mean every attempt to address a team or organizational problem must be super deep. Choosing the depth at which to intervene is critical for every manager, consultant, and coach.

What Is Depth?

What do I mean by depth? Depth is about how private, individual, and hidden the things you are trying to discover and influence are. I borrowed this term from Roger Harrison, whose ideas about “shallow” and “deep” inventions I’ve found useful as a coach and consultant. In his 1970 article “Choosing the Depth of Organizational Intervention,” he defined depth in this sense as “the extent to which core areas of the personality or self are the focus of the change attempt.”

Depth is a continuum. Public, external, and observable things like role definitions, work processes, and team behaviors are at the shallower end of the spectrum. Private, internal, and hidden things, like perceptions, attitudes, and feelings are at the deeper end. That isn’t to say that “shallower” interventions won’t provoke strong feelings. Harrison pointed out, “Issues of role differentiation, reward distribution, ability and performance evaluation, for example, are frequently invested with strong feelings. The concept of depth is concerned more with the accessibility and individuality of attitudes, values, and perceptions than it is with their strength.”

For example, in a project retrospective, I had the team build a timeline of significant events over the eighteen months they worked together. We displayed this on a long roll of butcher paper that ran the entire length of our largest conference room. Creating a shared view of what happened was a reasonably shallow – though useful – tactic. Most of the information in the timeline was available in project plans and shared calendars. It hadn’t been obvious, but it was all public information. Seeing it all together helped team members notice patterns they hadn’t before, giving them ideas for improving their process.

For example, in a project retrospective, I had the team build a timeline of significant events over the eighteen months they worked together. We displayed this on a long roll of butcher paper that ran the entire length of our largest conference room. Creating a shared view of what happened was a reasonably shallow – though useful – tactic. Most of the information in the timeline was available in project plans and shared calendars. It hadn’t been obvious, but it was all public information. Seeing it all together helped team members notice patterns they hadn’t before, giving them ideas for improving their process.

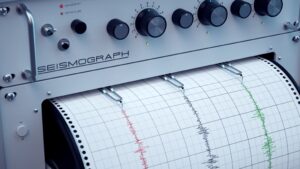

Next, I asked each team member to chart their emotional state during the project. They drew what we termed an “emotional seismograph” along the bottom of the paper. Each team member drew a different color of line, which went higher when they felt better and lower when they felt worse. This was a deeper move, bringing to the attention of the team things that had previously been private and hidden. The conversations these revelations generated led to different ideas for improvement than the original timeline had.

Why Does Depth Matter?

Whenever we try to help a person or group change, we intervene at some level of depth. For any given change, we almost always have multiple options for how to involve people. As managers, coaches, or consultants, we need to know how deep we are asking them to go. The depth we choose has three significant implications.

First, deeper interventions are more expensive. They require gathering more information. They can require 1-on-1 support methods – like coaching – because the change is more personal and individualized. Often, they take longer. You can’t change an entire department’s attitudes and feelings about another part of the organization overnight.

Second, deeper strategies require more buy-in from the people affected. I may want to help you change how you feel about and interact with a co-worker, but you must do the work. By definition, deeper changes are more internal. It doesn’t matter how much support I offer if you aren’t interested in investing considerable time and energy to make that shift happen.

Third, not going deep enough means the change doesn’t happen. While shallow interventions are cheaper, they run the risk of being ineffective. Sometimes a change requires that people shift their attitudes and approaches. Roger Harrison noted, “I believe that there is a direct relationship between the autonomy of individuals and the depth of intervention needed to effect organizational change.” The more freedom people have to act, the more likely a deeper approach is necessary.

How Deep to Go?

Given those implications, how do you decide how deep to go to help a change happen? Harrison suggests two criteria for choosing the appropriate depth of intervention:

[F]irst, to intervene at a level no deeper than that required to produce enduring solutions to the problems at hand; and second, to intervene at a level no deeper than that at which the energy and resources of the client can be committed to problem solving and to change.”

When I read this, I realized that many of my attempts to help teams had gone wrong because I hadn’t paid attention to these two guiding principles. I followed my preferences and ignored the situation I was in. Rather than operating at the shallowest level that might work, I started at the level of depth where I was most comfortable. (This was often at the level of interpersonal relationships and individual mindsets.) Whether or not the problem needed it, that is where I went. In most of those situations, I also didn’t assess if the people I was trying to help were ready to go that deep. When they weren’t, I just annoyed them – and I didn’t actually help solve the problem.

Since I started working with this idea of depth, I’ve had far fewer of those failures. When I’m aware that I have choices and follow Harrison’s recommendations, I’m much more likely to settle on a strategy that works. Given what I know about my tendency to go too deep too soon, I will often deliberately start with something that I think is “too shallow.” I really should stop being surprised when that works.

What Can You Do?

Think about times you’ve tried and failed to help a group change. As a manager, coach, or consultant, do you tend to go too deep or too shallow? What is your default strategy? What choices do you have for approaching it at a different level? If you took Harrison’s advice, what would that look like?