We require environments where people can provide input and ideas. If we limit engagement, we limit success. We still have organizations that either believe or act like they believe some types of workers are “stupid.” This idea dates back to the ideas surrounding Scientific Management, Fredrick Taylor, and Henry Ford. The concept of the stupid or unskilled worker that I mentioned was common in the early 20th century. In various writings about agile and agile ideas, we often refer to or see references to avoiding Scientific Management, Classic Scientific Management, or Taylorism. These management ideas limit engagement from people, which is going to limit success.

Understanding the past can be quite helpful to see where you might be able to improve today.

Scientific Management Overview

I will not attempt to summarize every detail of Scientific Management {SM = Scientific Management for sources}. There has been a ton written on the topic and you can read the book for more depth.

Fredrick Taylor published “The Principles of Scientific Management” in 1911 after working on the concepts for many years. Taylor focused on standardizing work processes so they are faster and more productive. He built on work that others had done before him. While Scientific Management did not survive, core ideas persist in today’s organizations.

- Management should maximize prosperity for the company and employees;

- Employers and employees have their destiny linked;

- Employers can’t prosper over the long term if employees are not prospering.

Taylor also talks about the benefit of training for employees so they can perform at their best. He championed breaks for workers so that they could be more effective and good pay for good work. He also focused on removing any waste from work processes. His recommendations derived from studying what people did. He observed, measured, and created the ‘most effective’ way to do work.

Some examples include:

- Instructing a bricklayer to pick up a brick with their left hand and trowel of mortar with their right is more efficient and reduces waste.

-

Analyzing and experimenting with shovel design, to allow workers to work longer without a break.

He believed that his focus on the best way to do a task would result in a better living for workers. Taylor begins the book with a reference to a speech by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908. Excerpts of the speech, titled “Conservation as a National Duty.” is below.

We have become great in a material sense because of the lavish use of our resources, and we have just reason to be proud of our growth. But the time has come to inquire seriously what will happen when our forests are gone, when the coal, the iron, the oil, and the gas are exhausted, when the soils shall have been still further impoverished and washed into the streams, polluting the rivers, denuding the fields, and obstructing navigation. These questions do not relate only to the next century or to the next generation. One distinguishing characteristic of really civilized men is foresight; we have to, as a nation, exercise foresight for this nation in the future; and if we do not exercise that foresight, dark will be the future! [First half of section 31]

Finally, let us remember that the conservation of our natural resources, though the gravest problem of today, is yet but part of another and greater problem to which this Nation is not yet awake, but to which it will awake in time, and with which it must hereafter grapple if it is to live–the problem of national efficiency, the patriotic duty of insuring the safety and continuance of the Nation. . . [First half of section 54]

Taylor saw in this speech that we must conserve our natural resources and importantly he saw the “waste of human effort” as a major issue {SM page 5}.

Problems with Scientific Management

There is value in ideas like reducing waste and experimenting to find ways to improve. However, the core of how Scientific Management accomplishes these is problematic and limiting.

Hierarchy

Scientific Management requires a “much more elaborate organization” {SM page 70}.

By Taylor’s calculations, spending extra money for overhead and management was cost effective. He saw that workers could produce more and make more money, even with the overhead costs. So he saw this as a beneficial approach {SM page 71}. We see remnants of this with hierarchy in organizations today. There are many layers between upper management and the people actually working to deliver value to customers. We see remnants of this with hierarchy in organizations today where there are many layers between upper management and the people actually doing the direct work to deliver value to customers.

Insulting Views — Bad Implications

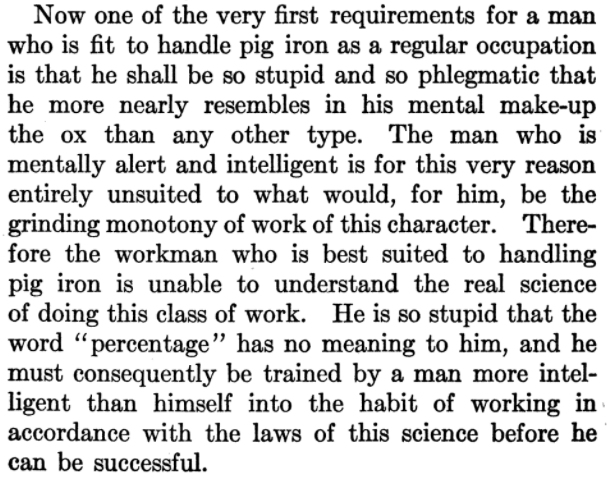

Taylor’s views of workers were often insulting — being condescending to workers he viewed as less intelligent, calling them stupid, and comparing them to animals.

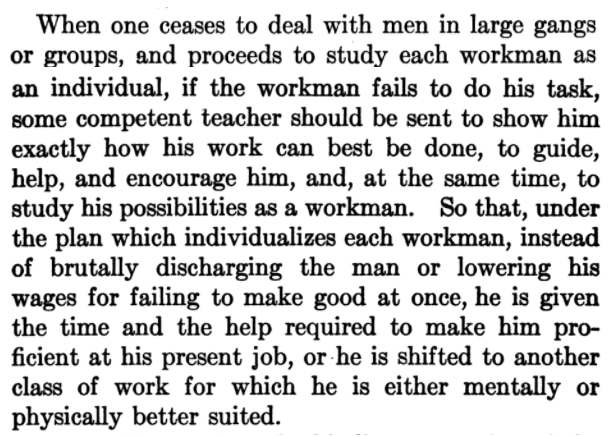

Taylor also has ideas that start off as something sounding more positive, such as training workers and helping them. However, a key part of his approach was based on his analysis of the persons intelligence, such as in the passage below.

We all have different skills, passions, and abilities in various areas. In management today, some still discount workers as lazy or worse without engaging them to understand or help. We also see assumptions about people limiting their value to the organization and team.

Individual Focus

Another issue with Scientific Management is its focus on individual measurement, not teams. While focusing on teams was uncommon, Taylor specifically focused on studying work that could be measured, broken into separate tasks, and recurred frequently. This type of approach does not hold up well in today’s team-based environments, where we know that people generally perform better if they are in high-performance teams.

Henry Ford

Ford did not cite Scientific Management as a source of inspiration. Yet, the dark side of this same thinking plays out at Ford with the Model T. People making the Model T were doing the same repetitive tasks. Henry Ford said he knew the number of distinct motions (7882) it took to make a Model T {Visit PBS to watch videos on the subject.}. The thinking centered on mechanizing humans.

Ford engineered skill out of the process so “anyone,” regardless of skill, could fill a position on the line. The process was so exhausting and monotonous that people would quit after a few days. If they needed 100 men, they needed to hire 1000 men to address turnover {PBS1}.

Ford was focused on creating processes that would work for unskilled workers, training them on one small operation. “Our foundry used to be much like other foundries. When we cast the first “Model T” cylinders in 1910, everything in the place was done by hand; shovels and wheelbarrows abounded. The work was then either skilled or unskilled; we had moulders and we had labourers. Now we have about five per cent of thoroughly skilled moulders and core setters, but the remaining 95 per cent are unskilled, or to put it more accurately, must be skilled in exactly one operation which the most stupid man can learn within two days.” {My Life and Work, by Henry Ford}

Years later (1928), his largest plant, the River Rouge Complex appeared like a machine.

You see Henry Ford trusting his security chief, Harry Bennett, to patrol the plant and force people to comply with the rules. “Bennett surrounded himself with a group of street fighters, athletes, ex-convicts, and underworld figures. With their weapons often prominently displayed, his men roamed the factory enforcing strict workplace rules. Workers were not allowed to talk or even sit down while on the clock. {PBS1}”

None of this is precisely what Taylor was calling for, yet the idea that people needed to function as machines or resources was the same. If management believes workers don’t know anything, how will things not deteriorate to a place where they are not trusted? How will the culture not simply turn into one of ‘listen and obey?’

We Need Engagement to Succeed

The idea that workers are stupid and can only perform simple tasks and that management is the only one who can think does not hold water today (or then, as it turned out). This kind of thinking, whether people call it Scientific Management or not, leads to organizations failing to adapt. It leads to organizations getting beaten by competitors (which is what happened to Ford when he would not listen to anyone).

We need engagement from everyone if we are going to improve continuously! We can’t afford to discount people simply because of the type of work they do. In Lean Thinking, we have the idea of ‘going to the gemba’ or ‘actual place’ where the work is happening. If we empower the teams doing the work to improve and engage, we gain so much more to drive results and build community.

Leadership must focus on creating an environment where people have the foundational safety and space to innovate, speak up, be creative, and exercise ownership and accountability over their work. At least if leaders want to improve, deliver value, and compete continuously.

How are you creating an organization that reduces fragility by engaging and learning from everyone? How are you limiting your options?

Excellent article! I was totally unaware of the Scientific Management concept, and this new information answers many questions I had been pondering. It explains the organization and layout of public schools, for example, in that warehouse structure, and the brutal suppression of individual thought and critical thinking. This also then explains the cultural habit of managing workers like mindless drones, and why it is so difficult to coach some individuals in management to abandon these long-held behaviors.

There are changes occurring now in public schools, to some extent, where there is at least a rudimentary move toward ‘encouraging’ free thought. And, due to the democratizing effects of the internet, the exploding Homeschool movement is reinvigorating the notion of students as self-guided, intelligent consumers of information who are capable of creating their own curriculum and encouraged to find their own research paths.

Similarly, Lean and Agile are revolutionizing the manufacturing and software development industries.

But often (in my opinion) it is in the Business side of the house where these notions are slowest to take hold. We can’t break out of this pattern until universities begin to teach business students a new management model.

Curtis, thanks for the comment! There is a lot of similar ideas that end up sounding a lot like these ideas. Public schools are an interesting one. There are many public schools that are using things that sounds a lot like agile, but they are not pulling those ideas from agile, they are coming from “what works”. For example, since kindergarten, my kids have done their OWN conferences. So instead of a parent-teacher conference, it has been a student-parent conference. The kids explain what they are doing and have done. Showing us the work. The teachers help them in advance to prepare, but the kids own the conference. Very interesting to listen to our kids explaining how they are doing. That is one of 100s of examples, but there are many schools and teachers and administrators who are introducing different ideas that make a huge difference. And I agree, that business side is slower, and some of that is because “software” has isolated itself (for some good reasons and some no as good). So we all need to play a part at sorting it out!

– Jake