You’re a mid-level manager in a rapidly growing company. Your boss tells you that a new initiative the company has been considering for the last year has finally gotten the go-ahead from the executive team. This initiative is similar to others your company has taken on in the previous few years, but it is different in a few key ways. There’s no playbook for work like this; success will require trying new things and learning from what happens. Your job is to pull together a team that will perform at a high level in challenging circumstances. What do you do?

The 60-30-10 Rule for Teams

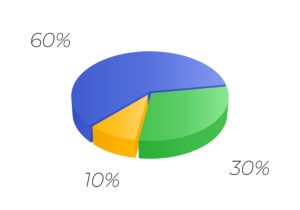

J. Richard Hackman estimated that “60% of the difference in how well a team eventually performs is determined by the quality of the prework the team leader does. Thirty percent is determined by how the initial launch of the team goes. And only 10 percent is determined by what the leader does after the team is already underway with its work.” Hackman called this the 60-30-10 Rule. He used the metaphor of a rocket: Its trajectory is largely set by the time it has left the launch pad.

J. Richard Hackman estimated that “60% of the difference in how well a team eventually performs is determined by the quality of the prework the team leader does. Thirty percent is determined by how the initial launch of the team goes. And only 10 percent is determined by what the leader does after the team is already underway with its work.” Hackman called this the 60-30-10 Rule. He used the metaphor of a rocket: Its trajectory is largely set by the time it has left the launch pad.

Hackman’s collaborator Ruth Wageman has written about using the 60-30-10 Rule as a guide to where managers should spend their time. If 60% of the difference comes from team design decisions before the team ever starts work, it makes sense to spend 60% of your effort there. The launch is when team members first learn about the purpose for which they have been brought together, the design of their work, and the skills and experience they each bring to the table. If 30% of the difference comes from how this is done, then managers ought to spend a proportional amount of time and energy on it.

Research by Hackman, Wageman, and others indicates that if managers want their teams to succeed, they should spend most of their time and energy before the team starts work and as the team launches. And yet, I rarely see this happen. Most thinking about team design concerns who goes on the team; surprisingly little is devoted to the nature of the work. Teams often start working with a sense of purpose that is neither clear nor compelling to the team. Team launches are treated as a luxury or an afterthought. In my experience, most managers concerned about team performance spend 90% of their time trying to influence the team’s development after it is underway – in the phase that only accounts for 10% of the variation in performance.

Setting Up a Team for Success

Hackman & Wageman’s research points to six team conditions that set the stage for high performance. They call them the three essential and three enabling conditions. These are:

- Real team

- Compelling purpose

- Right people

- Productive norms

- Supportive context

- Effective coaching

Using the 60-30-10 Rule is one of the most efficient ways to influence team performance. Before a team launches, pay close attention to the first five conditions. Consider the team’s shared objectives and how the team members will work interdependently. Draft a compelling purpose, test it, and iterate on it. Explore options for who will and won’t be on the team; you often have more choices than you think. Think about how you want them to work together so you are clear on “must do” and “never do” behaviors. Consider what types of support they will need from the organization and how they will get it.

Launching The Team

When getting ready to launch the team, spend more time than you think you need. If you’ve been following these guidelines, you’ve been thinking about this a lot – but this is the first time the team has seen it. You want to create a shared understanding of why you have set up the team the way you have. Be clear about what you need and get curious about what they think. Stay connected to them and be open to influence.

Make the new team a full partner in the launch process. Ask them to stress-test the thinking behind the design work you have done. Be ready to make tweaks based on what they come up with, and be firm about what is non-negotiable. Don’t launch the team without knowing that they understand what you expect, without them knowing that you understand their concerns, and without their commitment to working together in this way.

Monitoring and Coaching the Team

After the team launches, don’t ignore it but don’t be too involved. A team needs to learn a degree of self-management to become high-performing. The most valuable things you can monitor are three team processes: the team’s effort, how well its work strategy matches its situation, and how effectively it uses all its members’ expertise.

When one of these begins to falter, decide which type of coaching may help to get them back on track. A little nudge is often all they need when the team was set up for success with a solid design and a well-run launch.

Making Adjustments, Small and Large

What if that doesn’t work? Or if you find yourself in a situation where whoever set up the team didn’t use the 60-30-10 Rule, and the team wasn’t well-designed or strongly launched? If coaching isn’t moving the needle, your best bet is to look at the conditions you can influence. These are your levers for action.

Start by moving backward through the list. Can you address performance issues by getting them needed support or helping the team develop more productive norms? These types of interventions don’t require restructuring the group. Can you do a relaunch without changing who is on the team? I’ve facilitated many team resets, focusing on clarifying purpose, redesigning workflows, and reworking group norms. These set the team back on track toward high performance.

Or do you need to change team membership to address performance? In my experience, adding one person is the only possible “small” change to a team. Adding more than one – or removing one or more – means you have a new team. If you’re doing this, spend time redesigning and relaunching the team. Don’t just move people around and tell the team to figure out how to handle it. You have a new team, so use the 60-30-10 Rule to guide you. Otherwise, you’re likely to find yourself – and the team – back in the same place you started.

Successfully Managing Team Performance

It’s been a year since your boss asked you to guide the new initiative. Despite some pressure to kick off a team right away, you spent several weeks crafting the team’s purpose, shared objectives, and how its members would need to work interdependently to succeed. This was a new type of initiative for your company, and knowing your perspective was only one of many, you involved people throughout the organization in your design process. You considered different combinations of possible team members, thinking about not just task-based expertise but collaboration skills.

Once you decided who was on the team, you spent considerable time with them during their first weeks together as you launched the team. You introduced them to the business context spurring the initiative and what success looked like. You clarified who the team’s clients were and what they expected from the team regarding quantity, quality, and timeliness. With your prompting, the team members shared their concerns about these expectations, and together you considered how you might address them. You shared how you expected them to work together to achieve that success. Somewhat to your surprise, they had good suggestions for how to improve on your ideas. At the end of the launch process, you got a commitment from the team to the initiative, and you clarified how you would support them along the way.

The way was not always smooth. The initial enthusiasm from the launch faded as the team encountered early difficulties. You didn’t panic, however, as you saw that the team was still working hard, making appropriate adjustments to its work strategy, and bringing all of its members’ expertise to bear on the problem. After the first significant delivery of the team’s work, however, you noticed that the team fell into a rut. They stopped addressing issues with how they worked, and their overall level of effort fell. From their perspective, everything was “fine.” From their client’s perspective – and yours – it was not.

When you got curious about this, you found that they had essentially stopped talking to their customers and clients. Early on, they agreed that every team member would be involved in at least one interaction with an external stakeholder each week. Learning from the world outside the team had served them well leading up to the first delivery. Now that practice was being neglected. Some team members thought they knew everything they needed to complete the work. Clearly, they did not.

You worked with the team to revisit their ways of working, and they recommitted to their norm about working with external partners. This was the nudge they needed, and within a month, the team was back on track. They achieved five of the six primary goals of the initiative in less than the time expected – a major success in the eyes of the executive team. As importantly, each team member developed new skills and became an even more valuable part of the organization.

So it shouldn’t have been a surprise when your boss came to you at the end of the year and said, “The executive team has just approved this challenging new initiative, and they want you to put together a team to run with it…”