Conflict is a challenging topic for many people to navigate. It’s a natural part of working together in groups, yet in the midst of it, it can feel terribly dysfunctional. There’s no shortage of ideas about how to work through it, and there are lots of tools available. The choice of what tool to use when can feel overwhelming. How do you know where to get started? One of my to-go methods for engaging with conflict is the Waterline Model.

Conflict is a challenging topic for many people to navigate. It’s a natural part of working together in groups, yet in the midst of it, it can feel terribly dysfunctional. There’s no shortage of ideas about how to work through it, and there are lots of tools available. The choice of what tool to use when can feel overwhelming. How do you know where to get started? One of my to-go methods for engaging with conflict is the Waterline Model.

I’ve written about Roger Harrison’s guidelines for working with groups at the right level of depth. John Scherer and Ron Short, faculty members at the Leadership Institute of Seattle (LIOS), extended Harrison’s idea of depth into the Waterline Model[1]. Using this metaphor and practical tool increases my chances of helping a group navigate conflict by reducing the chances I’ll go too deep too soon.

Above and Below the Water

Think about the group as a boat moving along the surface of the water. When the group works above the water, they’re solving externally-facing problems. They’re thinking about customers, technology, money, quality, timelines, and other things that matter to people outside the group. This focus helps the group be productive, satisfy its clients, and achieve its goals.

When a group works well, the water is smooth, and they can focus on their tasks. The calmness of the water and the ease with which they move through it helps them be productive. But occasionally, the water gets choppy, seaweed tangles up the propeller, or barnacles clinging to the hull slow the boat down. When this happens, the group has a choice: keep going or address the disruption.

If they choose to address it, they must look below the water’s surface. Working below the waterline is different than it is above. Instead of thinking about tasks and content, this work focuses on processes and relationships. The goal is to keep the group healthy and functioning and to restore lost productivity.

The balance between these two types of work – task work and maintenance work – is critical. Where there is too little task work, the group isn’t productive enough to achieve its goals. The boat doesn’t move far enough fast enough. When there is too little maintenance, the group doesn’t have the productive capacity to accomplish its tasks. The condition of the boat prevents them from reaching their goal. The Waterline Model indicates that turbulence and breakdowns in task work are signs that maintenance work would be helpful.

So, what does this have to do with conflict? Conflict is a breakdown in the ability of the group to get things done. When issues below the waterline disrupt the group’s performance and threaten its health, that’s a conflict that’s risky to ignore.

How Deep to Go?

When a disruption occurs, you want to intervene at the shallowest level possible. Roger Harrison defined depth as “the extent to which core areas of the personality or self are the focus of the change attempt.” In terms of navigating conflict, trying to shift people’s attitudes and feelings about each other would be a deeper approach, while a shallower technique would be to clarify the group’s goals. Shallower methods are often easier and less expensive than deeper ones, but they risk being ineffective.

When a disruption occurs, you want to intervene at the shallowest level possible. Roger Harrison defined depth as “the extent to which core areas of the personality or self are the focus of the change attempt.” In terms of navigating conflict, trying to shift people’s attitudes and feelings about each other would be a deeper approach, while a shallower technique would be to clarify the group’s goals. Shallower methods are often easier and less expensive than deeper ones, but they risk being ineffective.

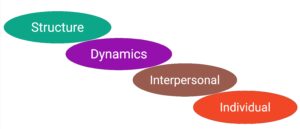

When I explain this concept to people, they tell me it makes sense. At the same time, they often want to understand what it looks like in practice. I find Scherer and Short’s work particularly useful for giving people something more concrete. The Waterline Model categorizes group issues based on where they arise and where they can be most usefully addressed. It arranges these categories into four levels based on their depth. Ordered from the shallowest to the deepest, they are:

- Structure

- Dynamics

- Interpersonal

- Individual

Let’s look at each of these in turn, examining what the level is, what conflicts that live here tend to be like, and what techniques for navigating conflict at this level might address.

Structure

A potential source of conflict that lives close to the surface is a group’s structure. An effective structure communicates a group’s purpose, goals, and roles. It also clarifies the context the group is part of, the resources it has access to, and the constraints it needs to operate within. When structure is well-established, people understand what the group is trying to accomplish and how they are expected to contribute towards those goals. Their roles fit together so they can perform their tasks effectively and efficiently. Group members know why they are doing what they are doing and what they have to work it. Structure largely determines whether or not a group works on the right things in the right ways.

A potential source of conflict that lives close to the surface is a group’s structure. An effective structure communicates a group’s purpose, goals, and roles. It also clarifies the context the group is part of, the resources it has access to, and the constraints it needs to operate within. When structure is well-established, people understand what the group is trying to accomplish and how they are expected to contribute towards those goals. Their roles fit together so they can perform their tasks effectively and efficiently. Group members know why they are doing what they are doing and what they have to work it. Structure largely determines whether or not a group works on the right things in the right ways.

Structure is a “shallow” level because it’s primarily concerned with information that is (or should be) public and shared rather than private and individual. Of course, a group’s structure might be ill-defined. Problems at this level manifest as confusion or disagreement about what the group is doing and how people’s work is supposed to fit together. Effective interventions at the level of structure include activities that create agreement around answers to questions like:

- Purpose: What is the group’s purpose? Why does it exist?

- Goals: What are its goals? What results is it expected to achieve? Why do those results matter to the larger organization?

- Roles: What roles exist within the group? Who is occupying each of those roles?

- Context: What else is happening in the organization that the group needs to know? In the larger world?

- Resources: What information will they need to perform their work and how will they get it? What expertise outside the group do they have access to? What equipment, supplies, and budget do they have to work with?

- Constraints: What constraints does the group need to work with? Where are the boundaries around possible actions? What is off-limits?

When conflict arises because of an unclear or problematic group structure, it’s not always apparent that the root of the problem lies at this level. It’s ubiquitous to see as a “personality conflict” between two people what is actually a difference in understanding their respective roles. One of the benefits of the Waterline Model is that it helps us to question our assumptions about the nature of a conflict – and what we can do to navigate it.

Dynamics

At a slightly deeper level than structure lives group dynamics. Dynamics is concerned with the patterns of interactions between everyone in the group. These patterns involve communication, participation, expectations, behavioral norms, accountability, decision-making, and conflict resolution. Dynamics considers how group members influence and learn from each other, how connected to the group they feel, and the levels of trust and safety within the group. Ultimately, dynamics affect how effective a group is at accomplishing its tasks.

At a slightly deeper level than structure lives group dynamics. Dynamics is concerned with the patterns of interactions between everyone in the group. These patterns involve communication, participation, expectations, behavioral norms, accountability, decision-making, and conflict resolution. Dynamics considers how group members influence and learn from each other, how connected to the group they feel, and the levels of trust and safety within the group. Ultimately, dynamics affect how effective a group is at accomplishing its tasks.

Clarity about how decisions will be made and by whom is a critical issue at this level. While some of the “by whom” is dictated by the roles that make up the group’s structure, there is wide latitude in how those decisions get made. How people are expected and invited to participate in decision-making impacts almost every other aspect of the group’s dynamics.

When a group has a problem at this level, it manifests as unproductive patterns. Participation and influence may be unevenly distributed. Members may refrain from offering their ideas or expertise to the group, even when it would be helpful. People may not know if a decision has been made or not. Some may feel like they aren’t really part of the group. Conflict at the level of dynamics arises either due to confusion about how the group members are expected to relate to each other or frustration about the current patterns. When these aren’t addressed, distrust, resentment, and “othering” often appear.

Dynamics isn’t as shallow as a group’s structure because at least a part of all of these interactions is personal and hidden. The patterns are observable, but many reasons why people engage the way they do aren’t. Intervening in a group’s dynamics requires deeper work than structural interventions do.

Interventions at the level of dynamics attempt to shift unproductive patterns to more productive ones. They involve identifying the types of interactions that are undermining group health and productivity and transforming them into ones that are a better match for the group’s situation. They may look at any of these areas and questions:

- Decision-making: How are different decisions made? How well are those decision-making methods matched to the problem they are trying to solve? How do group members know when a decision has been made?

- Effectiveness: How well-suited to its work is the group’s approach for accomplishing its tasks? How well is the group performing that work?

- Expectations & Accountability: Do people know what others expect of them? How do group members hold themselves and each other accountable? What happens when expectations aren’t met?

- Communication: What information needs to be shared? Do group members have access to the information they need from each other when they need it? How often are people “surprised?”

- Norms: What behaviors do group members expect from each other? What behaviors are out of bounds? What behaviors that violate the stated norms are tolerated (and from whom)?

- Conflict: What happens when group norms are violated? How are disagreements handled? What paths are there for escalation when they can’t be handled by the people directly involved?

- Participation & Influence: How are people invited to participate in the group’s work? How much of their knowledge and energy do they bring to it? How much of that is used? Where are the lines of influence in the group?

- Belonging & Inclusion: How strong is the group’s sense of identity? Who feels that they are part of the group? Who feels excluded?

- Trust & Safety: Who trusts whom to do what? Do group members question each other’s character or competence? How safe to take risks do group members feel?

As this list indicates, the number of potential issues and sources of conflict that reside at this level is enormous. There are also lots of tools for improving group dynamics. That may be why so many coaches and consultants focus here. One of the lessons of the Waterline Model, however, is that many conflicts that seem rooted in dynamics are actually problems of structure. Don’t dive to this depth until you know the group is fully aligned on purpose, goals, roles, and other structural questions.

Interpersonal

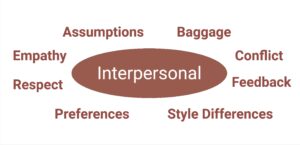

Deeper still than group dynamics is the interpersonal level. It focuses on the interactions between two people. It’s about how they communicate with one another and how they respond to 1-to-1 conflict.

Deeper still than group dynamics is the interpersonal level. It focuses on the interactions between two people. It’s about how they communicate with one another and how they respond to 1-to-1 conflict.

There’s a strong tendency to see conflict always being interpersonal. As we’ve discussed, however, even conflict that seems like it lives here usually has its roots in other levels. Truly interpersonal conflict means that the people involved agree on the group’s goals, the roles each plays, how the group makes decisions, shares information, holds each other accountable, etc. – and that despite agreeing on all those, they still have problems working together. It generally involves misunderstandings, assumptions, and a lack of communication between two people. Unchecked, it often festers from avoidance into resentment.

How can you improve problematic or non-existent communication? Many effective interpersonal interventions focus on these topics:

- Assumptions & Baggage: What story is each person telling themselves about what the other person is doing? What unvalidated assumptions are they making about each other? Which of these assumptions comes from prior experiences that have nothing to do with the current situation?

- Empathy & Respect: How can each person involved see the other person as a reasonable, intelligent human being who is doing the best they can given the circumstances? What do they respect and appreciate about each other, even in the midst of their frustrations?

- Preferences & Style Differences: How many things they disagree about are questions of style rather than right and wrong? What personal preferences are each of them willing to make concessions on to help the group achieve its goals?

- Feedback: How can they ask for feedback from each other more often? How can they give feedback to each other more often? How can they truly take this feedback to heart?

- Conflict: How can they engage productively in conflict rather than avoiding it? When something goes wrong, how can they acknowledge and repair the damage?

This layer is deeper still than group dynamics because most of the information about the conflict lives in the two people’s heads. A breakdown in communication means that the people involved aren’t discussing the problem. The key here is that they don’t need to like each other. They just need to work together well enough to accomplish the task at hand to the level of quality required. To do that, they need to bring the conflict out in the open where they can address it.

Individual

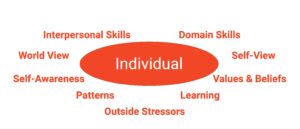

The deepest level in the Waterline Model is the individual. Fundamentally, the individual level is about how a person experiences working together in a group, how they behave as a result, and how effective they are in learning from that experience. This level is the most personal and hidden. Conflicts here are rooted in the person’s inner life and how they see themselves and the world around them.

The deepest level in the Waterline Model is the individual. Fundamentally, the individual level is about how a person experiences working together in a group, how they behave as a result, and how effective they are in learning from that experience. This level is the most personal and hidden. Conflicts here are rooted in the person’s inner life and how they see themselves and the world around them.

When interventions at the individual level are required, they often involve diagnosing (and then addressing) the specific challenge with questions like these:

- Skills (Domain & Interpersonal): Does the person have the knowledge and ability to perform their roles in the group? Do they have the interpersonal skills to work effectively in a group that is structured this way?

- Self-Awareness: Is the person aware of their behavior and its effect on the group? Do they see how they contribute to the group’s problems?

- Learning: Does the person learn from working together with other group members? Do they adapt and change their behavior as a result of what they learn?

- World and Self-View: Is there something about how they believe the world works that conflicts with what the group is trying to do? Does how they see themselves interfere with being an effective group member?

- Values & Beliefs: What does the person hold as important? Is a conflict of values within the group?

- Patterns: Are there recurring patterns of behavior that this person falls into with people in certain roles? Are there any “ghosts” from their past who keep showing up?

- Outside Stressors: Are there pressures and stresses from elsewhere in this person’s life that are affecting them? Are they anxious or overwhelmed because of things that have nothing to do with the group?

Truly individual issues are those that follow the person no matter what situation they are in. They manifest no matter how the people around them try to engage with them. Unsurprisingly, intervening at this level is challenging, and unless the individual commits time and energy to them, most individual interventions will fail to address the underlying issue. Often the only practical course of action is to remove the person from the group.

At the same time, most conflicts don’t require working at this level of depth to navigate. It’s very rare to have an entirely clear structure, well-developed group dynamics, and healthy interpersonal relationships yet to still have the group’s task work disrupted to the point that intervention is required. The vast majority of conflicts can be addressed at a shallower level.

“Snorkel Before You SCUBA”

Noticing the agitation and defensiveness that people displayed as a discussion became deeper and more personal, I came up with the idea of dealing with problems at the shallowest level at which they could be usefully addressed.”

Roger Harrison, Choosing the Depth of Organizational Intervention

We each have a level of the Waterline Model at which we feel most comfortable addressing conflict. My coach training taught me many tools for working with dynamics and interpersonal conflict. It’s no surprise that I reflexively start at one of those levels. The Waterline Model reminds me to check first and see if the problem lies at a shallower level.

Recently, I was asked to facilitate the creation of some working agreements for a new group in a company I was consulting with. The group was having trouble working together. They believed agreeing on norms and processes would reduce conflict. Before I knew about the Waterline Model, I would have dived right in. But in preparation for my first session with the group, I realized that “working agreements” is a dynamics intervention. Given my limited interaction with the group, I had no idea if their structure was clear.

I wanted to do my due diligence, so I started the first session with them by asking about their purpose, goals, and results. The group didn’t agree on why they were meeting and what results they were supposed to create. Unsurprisingly, they were having conflict, and developing working agreements wouldn’t have helped them. The group actually disbanded not long after because they realized there wasn’t a genuine reason for them to work together.

To effectively navigate a conflict, you might need to go deep. Some conflicts can only be effectively addressed at the interpersonal or individual level. The Waterline Model suggests that you start shallow and increase depth iteratively. Don’t start at the deepest levels. Or, as Scherer and Short put it, “Snorkel before you SCUBA.”

[1] Although Scherer and Short’s model is widely cited (and often erroneously attributed to Harrison), to my knowledge, they never published their work outside of LIOS. I learned it from Mary Beth O’Neill, a LIOS alum and former faculty member.

This is invaluable!

A really useful model, and unpacking of the model – thank you Paul!

Very insightful article! Thanks, Paul!