Working with other people is hard – for a variety of reasons. One of the promises of working together is that you can help each other to get things done. One of the biggest obstacles to doing this is not sharing a brain. Asking for clarity helps you avoid the trap of only thinking you know what someone wants. But all too often, when someone asks you for help or wants to delegate something to you, you can find yourself playing “Bring Me a Rock.”

Working with other people is hard – for a variety of reasons. One of the promises of working together is that you can help each other to get things done. One of the biggest obstacles to doing this is not sharing a brain. Asking for clarity helps you avoid the trap of only thinking you know what someone wants. But all too often, when someone asks you for help or wants to delegate something to you, you can find yourself playing “Bring Me a Rock.”

Management

Managing Up is about Partnership

For a long time, “managing up” rubbed me the wrong way. The way that people frequently used the phrase brought to mind judgment, manipulation, and deception. It seemed rooted in a belief that your manager didn’t understand how work got done. Just as I thought “stakeholder management” involved carefully controlling your messaging to always make yourself look good, I believed that managing up was fundamentally unethical.

For a long time, “managing up” rubbed me the wrong way. The way that people frequently used the phrase brought to mind judgment, manipulation, and deception. It seemed rooted in a belief that your manager didn’t understand how work got done. Just as I thought “stakeholder management” involved carefully controlling your messaging to always make yourself look good, I believed that managing up was fundamentally unethical.

I was wrong. Managing up is about partnership.

Unpacking Your Manager Role

Saying someone is a manager tells you little about what they do or where they spend their time. Different companies lay out these duties differently; managers within the same company (or department) sometimes have vastly different jobs. As a manager, having mismatched expectations about your role – particularly with your boss and peers – can have unfortunate results.

Saying someone is a manager tells you little about what they do or where they spend their time. Different companies lay out these duties differently; managers within the same company (or department) sometimes have vastly different jobs. As a manager, having mismatched expectations about your role – particularly with your boss and peers – can have unfortunate results.

Performance Feedback Requires Clear Expectations

“One of the people I manage is underperforming. I need to give them feedback about how they aren’t meeting expectations.”

I hear this often from managers, and I get curious whenever I do. The instinct behind it is good: Managers need to address underperformance. In my experience, however, giving performance feedback about unmet expectations is unlikely to help if you haven’t done your homework first. One of my teachers says, “80% of employee problems are due to manager neglect.” Whether you are a manager or not, when someone isn’t meeting your expectations, start by looking at what you’re doing – and what you’re not.

Navigating Team Conflict with the Waterline Model

Conflict is a challenging topic for many people to navigate. It’s a natural part of working together in groups, yet in the midst of it, it can feel terribly dysfunctional. There’s no shortage of ideas about how to work through it, and there are lots of tools available. The choice of what tool to use when can feel overwhelming. How do you know where to get started? One of my to-go methods for engaging with conflict is the Waterline Model.

Conflict is a challenging topic for many people to navigate. It’s a natural part of working together in groups, yet in the midst of it, it can feel terribly dysfunctional. There’s no shortage of ideas about how to work through it, and there are lots of tools available. The choice of what tool to use when can feel overwhelming. How do you know where to get started? One of my to-go methods for engaging with conflict is the Waterline Model.

Retrospectives Are Real Work, Too

“We don’t have time for a retrospective. We have ‘real work’ to do.”

“We don’t have time for a retrospective. We have ‘real work’ to do.”

How many times have you heard this? It comes up frequently in the classes I teach, I’ve heard it more times than I care to count. It frustrates me, and yet, I understand where it comes from. This issue isn’t limited to retrospectives. One of the challenges that managers, coaches, and consultants face is helping groups and teams to effectively balance productive work with work that builds and sustains their productivity. The key to that is understanding that working on the group’s functioning is also real work.

Communicating Change Effectively and Humanely

“I can tell this is hard for you all to hear. I know it’s harder for some of you than others. It’s not my first choice, either. However, it makes enough sense, and it’s the direction we’re going now. We’ll take some time to work through how we feel about this. Then we need to figure out how to start making this change.”

Those weren’t exactly the words the Director of Engineering used to communicate the change in our team’s priorities, but they are close. It was certainly the message that those of us in the room heard when he told us about the abrupt shift in the direction we were about to make. This potentially disruptive change was one of my first experiences with communicating change effectively and humanely. Because of how the director held himself and the team during the ensuing conversation, what could have been an absolute mess turned into a surprisingly positive experience.

Share Information, Not Anxiety

“I don’t want to distract the team. They don’t need to worry about this.” That’s what my boss – the head of engineering at a rapidly growing startup – told me when I asked him how he would share information from top management about our revised expansion plans. His job, he said, was to protect the engineers from things like this and to let them focus on building the product.

“I don’t want to distract the team. They don’t need to worry about this.” That’s what my boss – the head of engineering at a rapidly growing startup – told me when I asked him how he would share information from top management about our revised expansion plans. His job, he said, was to protect the engineers from things like this and to let them focus on building the product.

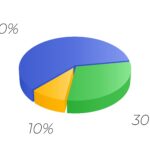

Managing Team Performance with the 60-30-10 Rule

You’re a mid-level manager in a rapidly growing company. Your boss tells you that a new initiative the company has been considering for the last year has finally gotten the go-ahead from the executive team. This initiative is similar to others your company has taken on in the previous few years, but it is different in a few key ways. There’s no playbook for work like this; success will require trying new things and learning from what happens. Your job is to pull together a team that will perform at a high level in challenging circumstances. What do you do?

Leadership Isn’t About You

Managers everywhere struggle to lead teams. These teams don’t produce the desired results, leaving everyone frustrated. A common cause of this problem is managers falling into the trap of thinking that leadership is about them. When this happens, a change in perspective can help them regain effectiveness.