Saying someone is a manager tells you little about what they do or where they spend their time. Different companies lay out these duties differently; managers within the same company (or department) sometimes have vastly different jobs. As a manager, having mismatched expectations about your role – particularly with your boss and peers – can have unfortunate results.

Saying someone is a manager tells you little about what they do or where they spend their time. Different companies lay out these duties differently; managers within the same company (or department) sometimes have vastly different jobs. As a manager, having mismatched expectations about your role – particularly with your boss and peers – can have unfortunate results.

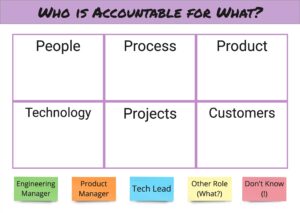

Areas of Accountability

One way of thinking about what a manager does and doesn’t do is by looking at different areas of accountability. In many technology organizations, for example, managers are accountable for one or more of the following areas:

-

-

- People

- Process

- Products

- Projects

- Customers

- Technology [1]

-

All of these areas are important for individual and team effectiveness. One person rarely handles all of them. In some organizations, for example, Engineering Managers are accountable for People, Process, and Technology, while Product Managers own Products, Projects, and Customers. In others, EMs are focused on People and Process, while a Tech Lead or Architect owns Technology decisions.

Many different arrangements can work; the key is agreeing on how they are arranged in your situation. This arrangement doesn’t have to be static; it can shift over time if you keep in sync with others. In Managing Amazing People, we use these “boxes” (as we sometimes call them) to help managers have two critical alignment conversations: with their manager and their peers.

Aligning with Your Boss

A key place to be clear on how you are arranging these accountabilities is with your boss. If you think that you don’t own Process, but your manager does, there will be problems. You can use this model to align with your boss and set clear expectations of each other. This is helpful when you start in a new role or when you start reporting to a different manager. It’s also useful whenever this working relationship needs a reset.

Rather than expect your manager to tell you which boxes you own, you may find it helpful to go into this conversation with a working theory. You can start with “Here’s what I think you’re holding me accountable for” and see if your sense matches your manager’s. If it does, that’s great! If it doesn’t, that’s also great! You’ve discovered a mismatch in your expectations that you can now address.

Agreeing on which boxes you’re accountable for is a good beginning, but don’t stop there. Develop a shared understanding of the answers to four additional questions:

- What does success look like in this area of accountability?

- How does that success support your boss in doing their job?

- How do they plan to support you in achieving that success?

- What other support do you need?

For example, you and your manager might agree that you are accountable for the People that report to you and the Process that the teams they are part of use. As you dig into what success in the area of People looks like, your manager shares that your department does not plan to hire any additional people in the next year (even though you doubled in size last year). Success in this area involves engaging and retaining your current people and helping them develop specific skills you need but don’t have the budget to hire for. You discover that the VP your manager reports to holds your boss accountable for several key business results that require closing those skill gaps. You don’t like this situation, but it does explain some of the demands your manager has been making of you. As you discuss what support you need and can expect in this area, you agree to check in on this topic in your weekly one-to-ones and to brainstorm ideas together when you feel stuck. Through this conversation, you set expectations about supporting each other to achieve the desired results.

Aligning with Your Peers

Another critical area for alignment is with your peers. Your areas of accountability are interlocking with other people’s. Discussing this interdependence with people who own the boxes you don’t can prevent problems. Again, it’s helpful to enter this conversation with a hypothesis – and to share it. Suppose you were starting in a new company as an Engineering Manager. In that case, you might begin one of these conversations with an experienced Tech Lead by sharing, “I’ve been assuming that I’m accountable for the People on this team and that you own Technology decisions. How does that match your understanding?” Along the way, you might discover that each of you thinks the other owns Process. A later conversation with your Product Manager counterpart might reveal similar confusion about accountability in this area. This is a clear sign that you need to address this misunderstanding.

The first step in aligning with your peers is agreeing on who is accountable for each area. Disagreements can either result in people stepping on each other’s toes (because they both believe they own that area) or work not getting done (because there’s an area no one owns). As before, however, this is only the first step. Working well with your peers requires having a shared understanding of:

- In this area, what does success look like?

- What higher-level goal does that result support?

- What support from your peers would be helpful?

- Where are you likely to experience tension between this area and those that others are accountable for?

Going back to the earlier example, imagine that you agree with your Tech Lead and Product Manager that you are accountable for People and Process, the Tech Lead for Technology, and the Product Manager for Products, Projects, and Customers. The three of you also check with your managers about this arrangement, and they agree that is what they expect from each of you.

As the three of you discuss what Process looks like, you discover that both of your counterparts have strong opinions about how the team should work. The Product Manager is relatively junior and hasn’t received much mentoring about effective collaboration in product development. They believe that because they are accountable for Products, it is their job to tell the team what to do. The Tech Lead, meanwhile, wants to be given a complete list of requirements before work starts so that they know all of the factors to consider when making decisions about Technology for the next two years. Neither of these is what the organization – and your manager – expects: a collaborative process with short feedback cycles. While they agree in principle that you own Process, you realize that without their feedback and buy-in, they will undermine your efforts to make the team effective. You don’t have a clear solution to this problem. Instead, you try to navigate these tensions by getting their agreement to experiment with different ways of working. You decide to check in weekly about how these are going. You are all aware that you might be working at cross-purposes, and you’re committed to finding a path forward.

Alignment is an Ongoing Process

These conversations with your boss and peers won’t prevent every misunderstanding about your role. Just as it’s helpful to enter each of them with an idea of the boundaries of your job, you should also treat the outcomes of these discussions as working theories. As you work together, you’ll discover where you thought you were aligned but weren’t. Revisiting these regularly – perhaps monthly or quarterly at first, then less frequently – will help you maintain clarity about your role as a manager.

[1] I’ve borrowed the “manager boxes” model from Jade Rubick’s Engineering manager vs. tech lead — which is better? as a way to think about the differences between different types of managers. “Technology” is a placeholder for whatever area you are working in. Feel free to substitute “Domain Expertise” for “Technology” if that seems more appropriate for your environment.