“We want to know how aligned people are around the new product development strategy. How can we do that?”

A group of senior leaders at a software company asked me this question as I was helping them to prepare for their annual kickoff meeting. They’d just completed a challenging year of development on a new product initiative. While it had generated some impressive results, they recognized that they needed to approach the following year differently. They were bringing the core team of twenty-five or so key contributors – usually distributed across the United States – together for several days to roll out their plans for the new year. They’d brought me in to help plan and facilitate the event. I knew what I needed to do: help them create a shared understanding of the new strategy.

A group of senior leaders at a software company asked me this question as I was helping them to prepare for their annual kickoff meeting. They’d just completed a challenging year of development on a new product initiative. While it had generated some impressive results, they recognized that they needed to approach the following year differently. They were bringing the core team of twenty-five or so key contributors – usually distributed across the United States – together for several days to roll out their plans for the new year. They’d brought me in to help plan and facilitate the event. I knew what I needed to do: help them create a shared understanding of the new strategy.

How Do We Know If We’re Aligned?

I’d gotten this request before. It’s a common concern for leaders: They’ve spent some time coming up with a plan that they are revealing to the team for the first time, and they want to know if their people are committed to carrying it out. (I talked about my experience doing this with a tool called Constellation with 120 people on an episode of the ORSC Lab on the Agile Uprising Podcast; the story starts around 23:19.)

Regardless of the number of people involved, I have found that discussions like these benefit from three distinct phases:

- Phase 1: Creating clarity around the actual plan

- Phase 2: Understanding people’s reactions to the plan

- Phase 3: Assessing people’s commitment to the plan

The danger is that the person bringing the plan often wants to jump to Phase 3. The first two create the shared understanding needed for the third to be meaningful. Asking how committed people are before ensuring everyone is talking about (essentially) the same thing – and what they think and feel about it – isn’t helpful. When you short-circuit the process, you don’t get an accurate answer to your question.

Creating Clarity

Knowing this, I proposed a structure for the opening and closing of the kickoff that would walk the group through these phases in order. The group planning the event was initially skeptical, but as I explained my reasoning, they saw how investing more time upfront would save them more time later. Here’s what we did.

At the beginning of the day, the leadership group introduced me as their facilitator. I told the team my job was to help them to achieve their goals for the event by making decisions about structure and process. I explained the process we were using and emphasized the importance of keeping these three steps separate. The leadership group would want to know the team’s reactions, but only after we were sure everyone knew what the leaders were planning.

We started Phase 1 with a short presentation from the primary sponsor of the work outlining the new strategy. In less than 15 minutes, he summarized the successes the team had achieved over the past year with the prior approach, how that approach would be ill-suited to the challenges they needed to address next, and what the strategy for the next year would be. He illustrated this with a few key examples, but it was mostly high-level. This brevity was by design; working out the details with the team was part of the plan for the kickoff. The sponsor had wanted to include more of what he thought some of those details would need to be, and I had coached him not to. If he wanted the team to get aligned and take ownership, he needed to leave room for them to make the plan their own.

When people encounter a change, their initial reaction is usually to a distorted version of what they hear. They filter their limited information through their hopes, fears, assumptions, and inferences. The first key to aligning is recognizing this is a natural process. You need to work with it. When presenting a change, you want to understand people’s responses to what you are actually proposing, not to what people are afraid you are suggesting. To do that, keep clarifying what you are talking about until you are sure they understand it well enough that their reactions are meaningful.

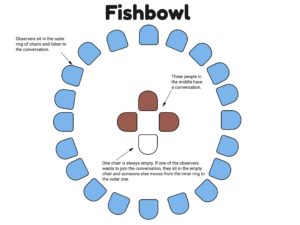

So, after the presentation, we moved into the first of several “fishbowl” activities. We had four chairs in the center of the room, with enough chairs in a ring around them for everyone to sit. The leader who had just made the presentation sat in one of the inner chairs. Anyone from the outer ring could come and sit in one of the three other chairs to ask him a question. The rules for this stage were:

- There must be one empty chair at all times (i.e., if two people were sitting asking the leader questions and someone new came in, one of them must leave)

- Ask questions to help you clarify your understanding of the new strategy.

I reminded people that we’d be asking for their reactions in the next phase; right now, we wanted to focus on understanding. I encouraged them to check their assumptions by asking what they thought the strategy implied. For example, one aspect involved shifting from a manual customer onboarding process to a more automated one. Did that mean the people hired to help with the onboarding process would be laid off? (The answer was “no”; they would shift to other work.) As the people in the inner chairs asked the sponsor for clarification, the people in the outer ring could hear the questions and the answers. This process continued for a while, with the sponsor providing the answers he had and clearing up misunderstandings as they arose.

Understanding Reactions

Once we felt that people were clear about the new direction and its implications, we moved on to Phase 2. The team knew enough about the actual strategy, so it was time for the sponsor to understand their reactions to it. At this point, the sponsor took a seat in the outer ring, and I took his chair in the inner circle. I invited people to sit in one of the other three inner chairs and share their reactions and reservations with me. I asked them to tell me what they thought about the approach. What parts excited them, and what did they have concerns about? I asked other people if they shared those excitements and hesitations. It wasn’t necessary to cycle everyone through the inner set of chairs to speak. Many of the reactions were shared by multiple people, so they didn’t need to. As we started to wrap up, I did ask for any responses that hadn’t yet been spoken, and a few more ideas came out.

To wrap up Phase 2, I invited the sponsor back into the inner ring and interviewed him again. He, of course, had listened to the team’s reactions and took notes. I asked him what he’d heard, and he summarized what people had shared. Did he think that the team had a clear understanding of what the new approach would entail? Yes, he did. What had it been like to listen to the team like that? How did he feel? What had surprised him? What had he expected the team to bring up that they hadn’t? I had prepared him for this part, so he didn’t argue with people’s concerns. He acknowledged them and mentioned a few potential changes he could make that might alleviate them. While he spoke, I watched – as well as I could – the people in the outer ring of chairs to see how this was landing. Did they have the sense that he understood their reactions and took them seriously? I sensed that they did, so we concluded Phase 2 here.

Assessing Commitment

Over the next day, the group worked together to address the concerns they had raised. They imagined it was a year into the future and that they had succeeded in meeting the challenge the strategy hoped to address. The team identified the key things they needed to do along the way. They also looked at things they were currently doing that would make it harder to meet the challenge and decided what they wanted to stop doing. These activities gave more opportunities for concerns to be raised and considered.

We concluded the kickoff workshop with a Constellation, which was Phase 3 in our alignment process. We asked each person to “take a stand” in response to three questions:

- “How clear are you on the strategy?”

- “How clear are you on how you can support the strategy?”

- “How strong are your reservations about committing to the strategy?”

For the first two questions, we asked people to stand closer to the center of the room the clearer they were, and more toward the edges the less clear they were. We debriefed these questions by asking to hear from people standing in various locations why they were where they were and what it was like to be there. For the last question, we asked people to stand further from the center the stronger their reservations. When we debriefed, we asked people to share their degree of confidence that their reservations could be addressed as the strategy unfolded. This process wasn’t a discussion; it was an opportunity for people to learn about the different perspectives in the group. We wrapped up by letting people know the next steps and thanking them for their involvement in and contributions to the workshop.

In my post-workshop follow-up with the senior leaders who had brought me in, I asked how much they got what they were looking for. They told me they had a much clearer idea of what implementing the strategy would entail, as the team had brought up several issues they hadn’t considered – and ways to handle them. The group expressed surprise at some people’s reactions – and admitted those reactions made sense when they thought about them. They knew that the team understood what they were moving forward with because the team had described it in their own words. They also had a clear idea of who was committed to the new strategy and who wasn’t yet. The Constellation at the end of the second day helped with this, but it wasn’t the only source of information. They’d also seen people’s commitment reflected in how they dug into the implementation planning process and worked with the objections raised. Not everyone was 100% supportive, but the leadership group knew where they stood and what they needed to do next.

Getting Aligned Through Shared Understanding

This story illustrates how I assess and foster alignment in a group. The kickoff workshop was a long-form, medium-scale example of the process. The three phases – create clarity, understand reactions, and assess commitment – can just as easily show up in a one-on-one conversation. The key questions to ask are:

- How do I know that we’re thinking about the same thing?

- How do I know that they know I understand their reactions?

- How committed to supporting this are they?

The first question focuses on creating a shared understanding of the idea. The second deals with a shared understanding of what people think and feel about the idea. Both are important, and the order is essential. People often want to skip over the first two steps, but they are critical to getting a real sense of commitment. If you want to gauge – and create – alignment, start by creating shared understanding.