Authority is a defining feature of a manager. By definition, managers can do things that others can’t do simply by virtue of their role. This power is neither good nor bad on its own. Unfortunately, many managers are ambivalent about their positional power. This unease hinders their ability to use it well. As a manager, owning your authority means you must come to terms with it.

Authority is a defining feature of a manager. By definition, managers can do things that others can’t do simply by virtue of their role. This power is neither good nor bad on its own. Unfortunately, many managers are ambivalent about their positional power. This unease hinders their ability to use it well. As a manager, owning your authority means you must come to terms with it.

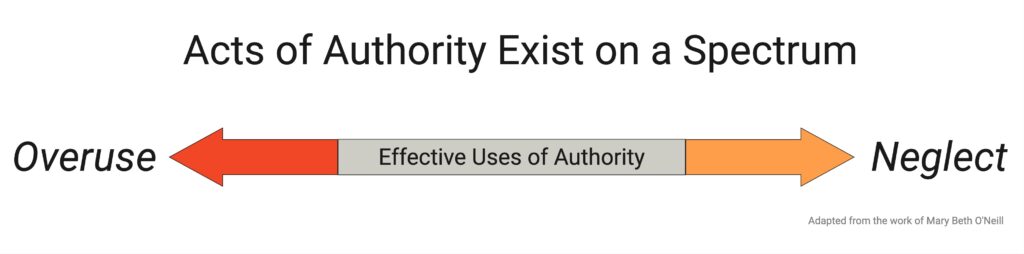

Effective managers exercise their positional power without overusing or neglecting it. They invoke it when needed and use it to help necessary things get done. As a manager, acknowledging four things about your authority can help you own it so it doesn’t own you.

Recognize your baggage about using authority

Many of us have worked for managers who overused – or abused – their positional power. They might have given us detailed instructions to follow rather than delegating decisions to us. Maybe they perceived questions as a challenge to their authority. Or perhaps they asked for status updates more often and in more detail than we thought was reasonable. We saw how they squandered the talents of those who worked for them, and we remember how that felt. We swore that we would never do that to anyone else.

The problem is when you let the pendulum swing too far in the other direction. You can fail to delegate well because you don’t set clear expectations. You can spend far too much time convincing people what needs to be done – even though a decision has already been made – because you worry about being thought of as controlling. Out of fear of marginalizing others, you can marginalize yourself. You might focus so much on helping people to be heard that you never give them something to agree with.

What can help is seeing “overuse vs. neglect authority” as a spectrum instead of a binary choice. If you’ve been on the receiving end of overuse, you probably tend toward the “neglect” end of the scale – particularly under stress. Most of the time, however, the helpful place to be is somewhere in the middle. The challenge is that even the tiniest step toward the middle can feel like it will cause you to overshoot and misuse your authority. In reality, you’re likely so committed to never landing there that there’s no chance of that happening. Still, you won’t trust that until you’ve done it enough times. Learning to explore the expansive middle of this spectrum is what coming to terms with your authority is all about.

Recognize neglecting your authority is not harmless

Coming to terms with positional power involves learning that not every use of authority involves abusing it. It also means recognizing that avoiding its use is not harmless.

Here are some ways I’ve seen managers abdicate their authority and the harm they caused. (The names are made up, but the situations are real.)

- Avery’s staff was supposed to send in their updates and agenda items 24 hours before the weekly staff meeting. But Avery didn’t enforce this, so instead, the group spent the first twenty minutes of the meeting each week updating the agenda. Avery was frustrated with this… and wasn’t the only one.

- Billie’s direct reports were expected to resolve disagreements between themselves. But when they couldn’t and escalated to Billie to make a decision, Billie told them to “figure it out” amongst themselves. Eventually, no one brought conflicts to Billie… they just let them linger.

- Cameron wanted the team to feel like they had autonomy about what projects they worked on. Whenever it came time for the team to make a choice, Cameron would “sell” them on the right one – the one Cameron’s boss had said was most important. Cameron was exhausted by “convincing” the team to take on work… and maintaining the charade that they had a choice about it.

- Dylan liked investing in people with potential. Dylan would hire people into roles that were a stretch for them and give them a chance to grow. Unfortunately, Dylan wasn’t good at coaching people or telling them they weren’t meeting expectations. Dylan developed a reputation for letting “nice” people hang on in the wrong role for too long. Dylan’s high-performers resented this drag on their productivity… and until they left for places with higher standards.

Most managers who are reluctant to use their authority to set standards, enforce consequences, and make decisions do so out of a sense of care for others. The irony is that avoiding these things sometimes causes more harm than good.

Recognize you have options

Managers often struggle to embrace their authority when they engage in binary thinking. The belief that their only choice is either making a unilateral decision or letting the group decide can make them hesitate to invoke their decision rights. However, effective managers understand that they have many options for using their authority to serve both the group and the situation.

Managers often struggle to embrace their authority when they engage in binary thinking. The belief that their only choice is either making a unilateral decision or letting the group decide can make them hesitate to invoke their decision rights. However, effective managers understand that they have many options for using their authority to serve both the group and the situation.

Most uses of authority aren’t binary. They exist on a spectrum. Take decision-making, for example. At one end of the spectrum is a unilateral decision made and announced by the manager. On the other is a group decision made by complete and enthusiastic agreement by everyone involved. There are many stops between these two endpoints. As a manager, you might ask for everyone’s opinion, then announce your decision. You might present a proposal to the group and ask for their reservations and level of commitment to carrying it out. Another option is letting the group decide by majority vote, where your ballot is just one among many. You can let the group develop a proposal they think is best for you to ratify or veto. You can even set a time constraint: “If we haven’t decided as a group in the next two hours, then I will make the decision based on what I’ve heard.”

When you know you have more than two choices about using your authority, you’re more likely to choose one that works for you, your people, and the situation.

Recognize that it isn’t just you

Much of our difficulty with power comes from larger cultural influences. Many of us have worked in places that are just as conflicted about the use of authority as we are. Ironically, while positional power makes a manager a manager, many organizations caution us against using it. As Allison Pollard has pointed out, it’s as though we give managers positional authority and then tell them, “Now, don’t use that.” We often don’t have good role models for this behavior. It shouldn’t be surprising that we’re hesitant to use it – and that we struggle to use it well.

Much of our difficulty with power comes from larger cultural influences. Many of us have worked in places that are just as conflicted about the use of authority as we are. Ironically, while positional power makes a manager a manager, many organizations caution us against using it. As Allison Pollard has pointed out, it’s as though we give managers positional authority and then tell them, “Now, don’t use that.” We often don’t have good role models for this behavior. It shouldn’t be surprising that we’re hesitant to use it – and that we struggle to use it well.

When we’ve heard “leaders good; managers bad” so many times, it’s no surprise that we don’t want to “act like a manager.” Overusing managerial authority is a problem, but so is avoiding using it when appropriate. Effective managers avoid both these traps by coming to terms with their authority.