“One of the people I manage is underperforming. I need to give them feedback about how they aren’t meeting expectations.”

I hear this often from managers, and I get curious whenever I do. The instinct behind it is good: Managers need to address underperformance. In my experience, however, giving performance feedback about unmet expectations is unlikely to help if you haven’t done your homework first. One of my teachers says, “80% of employee problems are due to manager neglect.” Whether you are a manager or not, when someone isn’t meeting your expectations, start by looking at what you’re doing – and what you’re not.

Am I Clear About What I Expect?

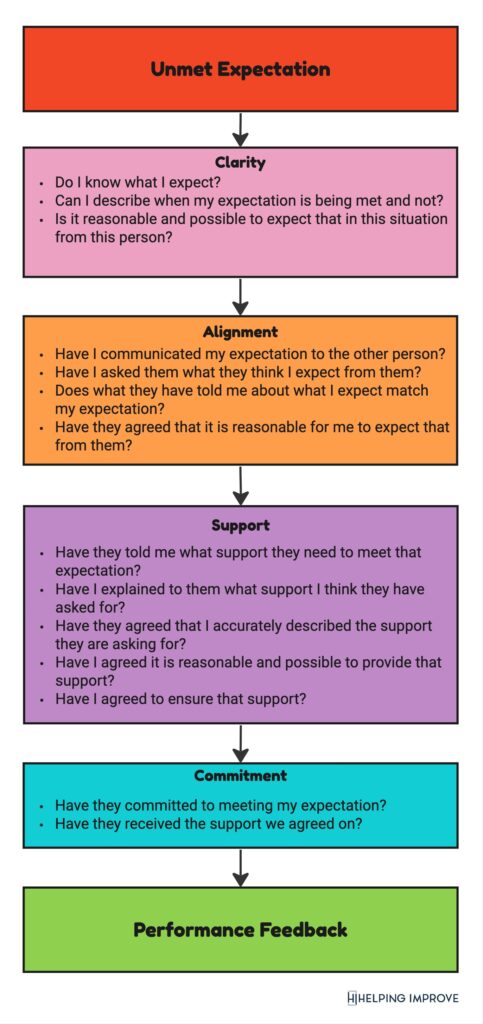

Your first indication that someone isn’t meeting your expectations is likely a general sense of “That’s not what I want.” When I coach managers about underperforming employees, they often struggle to describe what they actually expect from the person. At first, they can only say, “Well, I didn’t want that.” If you can’t describe what you want someone to do, it’s unlikely they know you’re expecting that from them. Before you rush to give them feedback, ask yourself:

- Do I know what I expect?

- Can I describe when my expectation is being met and not?

- Is it reasonable and possible to expect that in this situation from this person?

If you can’t answer “Yes” to all of these questions, feedback will probably not give you the result you are looking for. Instead, spend time working out what you want. Giving useful performance feedback requires you to describe clearly what you’re looking for and what you’re getting instead.

Are We Aligned on What I Expect?

Just because you know what you expect from someone doesn’t mean they understand. And much to many people’s surprise, even if you said something to them doesn’t mean they know it. (The most common answer when I ask, “How do you know that they know what you expect of them?” is, “Because I told them.”) Being aligned means that you both have a similar enough idea about what you expect of them. If you think that’s true, ask yourself these questions:

- Have I communicated my expectation to the other person?

- Have I asked them what they think I expect from them?

- Does what they have told me about what I expect match my expectation?

- Have they agreed that it is reasonable for me to expect that from them?

Again, if you can’t answer “Yes” to all of these questions, performance feedback probably won’t help. Instead, you may want to have a conversation that starts with, “I’m sorry. I wasn’t clear about what I was expecting. What you did isn’t what I wanted, but you couldn’t have known that, so that’s on me. Let’s talk about what I do want for next time.” (You might consider this a type of feedback, but it’s probably not what you originally had in mind.)

Am I Clear About What They Need From Me?

People’s ability to meet our expectations is rarely unconditional. Consider:

- “I can have the finance report to you by Friday if you get me the budget projections by Tuesday.”

- “I can plan and facilitate the staff retreat if the two of us can clarify the outcomes you want.”

- “I can take over the operations role next year if I can complete these three safety trainings and certifications in the third quarter.”

When we expect something from someone, we easily forget that we play a role in their ability to fulfill it. They may need something task-oriented, like budget projections. They may need further clarity about what we expect, like understanding the desired outcomes from the staff retreat. Or they may need to develop skills and competence through something like training.

As a manager, giving someone feedback isn’t a “get out of jail free” card for your own mistakes. Have you been setting them up for success? When someone who is clear about your expectations isn’t living up to them, consider your part in creating conditions where they could meet them. Ask yourself:

- Have they told me what support they need to meet that expectation?

- Have I explained to them what support I think they have asked for?

- Have they agreed that I accurately described the support they are asking for?

- Have I agreed it is reasonable and possible to provide that support?

- Have I agreed to ensure that support?

If you can’t answer “Yes” to all of these questions, giving performance feedback is unlikely to help. What’s useful instead is curiosity. Get curious about what you might be doing or not doing that’s making it harder for them to do what you’re asking. Find out what support would be useful to them, and then take action on that.

Are We Both Committed?

Asking for commitment is a critical part of setting expectations. It signals, “Now I actually expect this from you.” It’s also important not to ask for a commitment until the other person is clear on what they need to do. “Agreement in principle” is not a commitment. You might agree with the intent of what I want and still not be willing to commit to the action I’m asking you to take. If you’ve aligned with someone about what you each expect from each other and they still aren’t meeting your expectations, ask yourself:

- Have they committed to meeting my expectation?

- Have they received the support we agreed on?

Every so often, I’ll have a conversation with someone in which we agree on what I want and what support they would need from me to do that… and then nothing happens. Usually, when I look back at this, I realize that I never asked them to commit to doing it. They thought we were still negotiating, while I thought we had agreed to move forward. Oops.

Of course, as part of setting clear expectations, you agreed to support the other person in specific ways. If that support hasn’t arrived, you shouldn’t be surprised if they aren’t performing up to expectations.

Being Clear and Getting Curious

If you’ve gone through these questions and answered “Yes” to all of them, then it is time for a conversation. Even then, it’s helpful to stay curious. Effective feedback is grounded in mutual purpose, and curiosity helps reinforce that. Many of my performance feedback conversations have started with a short statement and a simple question. The statement is essentially, “I think this expectation isn’t being met.” That might sound like this:

- “Two weeks ago, you told me I would have the finance report by last Friday, and I haven’t seen it yet.”

- “We met last week to clarify the outcomes I wanted from the staff retreat, and I don’t see those reflected in this plan.”

- “As part of your PIP, you agreed to improve how you communicate with the rest of the team, but the comments you wrote in the document review last week are the same problematic statements you said three weeks ago that you would stop making.”

The follow-up to that short, clear statement is a question like, “What’s going on?” There’s a disconnect somewhere, and I want to know where it is before I give feedback. I might even ask, “Do you think this is what I expect?” If the person I’m talking to thinks they’re meeting my expectations, I need to make them aware that they aren’t, and we need to recalibrate. On the other hand, if they know they’re falling short, then what they need from me is different. If I come into the conversation without having done my homework – if I assume they are to blame – I’m unlikely to give feedback that improves the chances that I’ll get what I want. Addressing underperformance is a two-way street.