Addressing complaints is essential to a manager’s job but can quickly become overwhelming. Part One of this series shared a technique for sorting through people’s concerns. It also showed how to use your authority effectively to address some of them. But people often complain about things outside your control – and you need to deal with those as well.

Addressing complaints is essential to a manager’s job but can quickly become overwhelming. Part One of this series shared a technique for sorting through people’s concerns. It also showed how to use your authority effectively to address some of them. But people often complain about things outside your control – and you need to deal with those as well.

Move Beyond Authority

While some managers struggle to use their authority effectively, others don’t hesitate to act in situations under their control. These managers sometimes want expanded power to address a broader range of issues. “If I were in charge, we wouldn’t have this problem,” they say.

That may or may not be true. (It’s remarkable how seemingly simple issues reveal themselves as far more complex when we fully understand them.) Regardless, managers often need to address complaints that lie beyond their authority. As I said in Part One, effective managers can work with challenges they can only influence. That article shared two approaches to addressing complaints close to the center of the Circles & Soup diagram: Decide and Act and Announce Intent and Manage Up. In this article, we’ll look at how managers can expand their range by mastering two more techniques:

- Advocate and Seek Support

- Embrace the Constraint

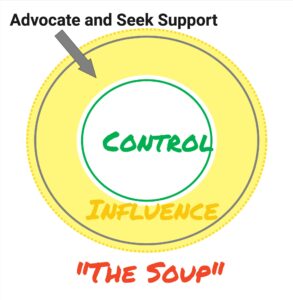

Advocate and Seek Support

As you reach the limits of your authority, one approach you can consider is to Announce Intent and Manage Up. This technique applies when you can implement the decision but you’re not fully empowered to make it. However, this method doesn’t work when you need someone else to act to address the problem. In that situation, you have to Advocate and Seek Support.

Your people often do this when they bring a problem to you. Most of the time, if they could address it themselves, they would. The solution might be in your Circle of Control, but it’s in their Circle of Influence. They need more than a decision from you; they need you to take action to address their challenge. They try to advocate effectively for their idea to get support from you.

Being an advocate requires influencing others. Being an effective advocate involves more than just pointing out that there is a problem. It’s easier to advocate for a specific solution to a complaint. Before you try to persuade someone to support your idea, get very clear about what the support you need is. Clarifying what you’re looking for helps you identify the right person to influence. Once you know what you’re asking for and who to get it from, you must connect the problem to something they care about. Influencing someone means talking about things that they value. If you can’t explain why it is in their interest to give you the support you need, you are unlikely to persuade them to help.

About ten years ago, I was an engineering manager in a large corporation exploring agile practices and methods. We had run two pilot projects using Scrum – one very successful and the other less so. Several people in my office were working on another project that claimed to be using Scrum, but from their complaints about it, it was clear they weren’t. The project team was split across several locations on three continents, with the manager in charge based in Europe. In December, I discovered that I (along with most other engineers in my office) would join the project the following summer to work on the product’s next major release.

My manager and I realized this would be an excellent opportunity to address the complaints we were getting about how the team was (or wasn’t) using Scrum. The person we needed to influence was the program manager in charge. We saw our chance when he visited our office in the spring of that year. We scheduled time with him to talk through how the new team would be structured and how they would work together.

In that conversation, we asked the program manager what worked well with the current process and what he wanted to change. We also asked some pointed questions about how the team implemented specific parts of the Scrum framework. It became clear as we talked that what the team was doing bore little resemblance to what is described in the Scrum Guide. The program manager was frustrated with the quality level of the product and how the project timelines kept slipping. When we mentioned the recent successes we’d had delivering on time and with a high level of quality, he invited us to explain what we’d done. After a brief whiteboard session, in which we’d piqued his interest in our methods, he agreed we should meet again to discuss introducing these processes when we joined the project that summer.[1]

The program manager’s support was critical to changing how the team operated. Neither my manager nor I could have sponsored the change on our own. Just forwarding the complaints we were getting from the team wouldn’t have worked either. We needed to show how working differently would benefit him and align with his goals. We worked together for the next three years, and it was clear how our changes helped everyone involved. None of that would have been possible without our advocacy and his support.

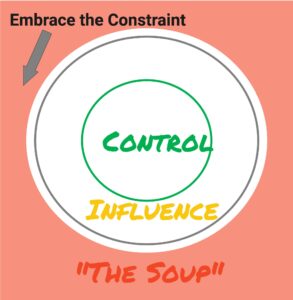

Embrace the Constraint

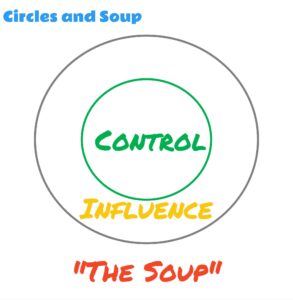

No matter how persuasive and well-connected you are, there will always be things you can’t change. In the Circles & Soup model, the area beyond your control and influence is the Soup. Why? As Diana Larsen explains:

I borrowed the useful concept of “The Soup” from David Schmalz, all those elements of organizational climate & culture, policies & procedures, and other systemic factors in organizations that have become so embedded in “the way we do things around here” that the team has little hope of shifting them without considerable help and political will on someone’s part.”

Teams usually should stay out of the Soup, as they have little chance to do anything about problems arising from it. Managers, unfortunately, often need to navigate the Soup. Because you can’t change everything you want in the Soup, the most effective strategy I’ve found is to Embrace the Constraint.

Embracing the constraint involves determining which parts of the situation are fixed versus those that only seem to be. The Soup is rife with bureaucracy, which is usually not worth challenging. At the same time, I’ve seen many bureaucratic problems stem from interpretations of policies rather than the policies themselves. The key to embracing the constraint is to find the smallest thing you can’t change and then give yourself as many degrees of freedom to mitigate its effects as possible.

I’ve written before about working within the constraints of a company’s stage-gated project approval process and using feature budgets to move away from fixed requirements. We embraced the constraint of the Project Planning Group (PPG) structure. In the process, we discovered that not all of the pieces of the process were required. At a recent Open Space conference, I convened a session about “Strategies for the Soup,” where participants shared stories of how they worked within systems and policies they couldn’t change. All of these shared an essential element with Advocate and Seek Support: They focused on understanding what the other people involved cared about.

One manager shared how this group complained repeatedly about a cumbersome, HR-imposed policy. He figured out who the right person in HR to talk to was, and he got curious about what parts of the policy mattered to them. The HR leader told him that his group didn’t care about the process everyone else used to collect the information – which was the burdensome piece that this manager objected to. The HR group needed the data that resulted from the process. The manager could use whatever process he wanted to gather the data as long as it was submitted in the required format by the specified deadline. If it were up to the manager, he wouldn’t have to report the data. By understanding what HR needed, he could embrace the constraint and develop an easier-to-use process for his group.

Saying No

Between Part One and Part Two, I’ve covered four approaches that managers can use for addressing complaints:

- Decide and Act

- Announce Intent and Manage Up

- Advocate and Seek Support

- Embrace the Constraint

It would be wonderful if, as managers, we could handle all of our people’s concerns and complaints by using our authority or influence. There are times when we either can’t change things or we choose not to. How to handle those situations skillfully is the topic of Part Three.

[1] I knew we had been good advocates when the program manager looked at me, nodded, and said, “Yes, I would like to buy some Scrum.”