Addressing complaints is an essential part of a manager’s job. By keeping their finger on the pulse of what’s bothering people, managers can act as an early warning system for higher levels of management. By addressing their people’s concerns, managers can improve both productivity and morale. At the same time, facing an endless stream of criticism – often about things you can’t control – can be one of the most frustrating parts of being a manager. As a manager, you need the ability to listen to and learn from complaints without drowning in them.

Addressing complaints is an essential part of a manager’s job. By keeping their finger on the pulse of what’s bothering people, managers can act as an early warning system for higher levels of management. By addressing their people’s concerns, managers can improve both productivity and morale. At the same time, facing an endless stream of criticism – often about things you can’t control – can be one of the most frustrating parts of being a manager. As a manager, you need the ability to listen to and learn from complaints without drowning in them.

Sort Complaints into Circles & Soup

When I work with managers flooded with complaints from their people, I turn to Circles & Soup. One reason I use this thinking tool so often is its flexibility. With teams, I usually use it as a prioritization tool. Asking them to concentrate on things under their control increases their sense of efficacy. Managers, however, need to become adept at identifying the limits of their decision-making authority and working with challenges they can only influence. Circles & Soup can be a tool for sorting complaints and finding appropriate methods for action.

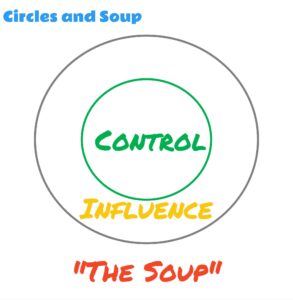

As its core, Circles & Soup is a simple drawing of two concentric circles, which divides the diagram into three regions. The area inside the inner circle is labeled “Control.” The region outside that circle but inside the other one is labeled “Influence.” Finally, the space outside both circles is labeled “The Soup.”

Imagine, as a manager, collecting your people’s complaints and sorting them into three categories – Control, Influence, and the Soup – placing them onto the diagram as you did so. Near the center, inside the Circle of Control, would be things you could address by making and carrying out a decision. Further away from the center, outside the Circle of Control but inside the Circle of Influence, are things you need to influence or persuade others to do. Finally, outside both circles are those things that no one you know can effectively control.

The closer you are to the center, the more you have the power to simply decide what to do. The further out you go, the more you have to make recommendations and influence others who can make those decisions. And at some point, there’s really no one who can make those decisions.

As I mentioned, when I use this tool with teams, I encourage them to concentrate on the items close to the center. However, managers must learn to work effectively with challenges everywhere on the diagram. I’ve found five practical approaches to addressing complaints. Those approaches are:

- Decide and Act

- Announce Intent and Manage Up

- Advocate and Seek Support

- Embrace the Constraint

- Acknowledge Impact, Share Context, and Do Nothing

This article describes the first two approaches; the next two are covered in Part Two, and the final technique is discussed in Part Three.

Decide and Act

For those complaints that fall close to the center of your Circle of Control, a practical response is “decide and act.” I once worked for a Vice President of Engineering whose weekly staff meeting was inconvenient for everyone who attended – except him. At first, he thought there was nothing he could do about this, but eventually, he decided to move the meeting time. He had constraints on that decision – like other meetings on his calendar – that he would also need to rearrange. He consulted us about our constraints and preferences for the new time. Ultimately, the timing of this meeting was under his control; none of us could change it. He could address people’s complaints by making a decision – perhaps in a consultative way, perhaps unilaterally – making that decision clear, and carrying it out.

Addressing problems by deciding and acting requires you to be willing to stand in your authority. I’ve worked with managers who were reluctant to do so. I worked with a director who was frustrated by her staff meetings. They were unproductive partly because she didn’t insist on good meeting practices, like having an agenda and clear action items. Her discomfort with authority meant she avoided setting expectations about these practices. She denied she had the power to change things, saying, “I really want the team to take ownership of this meeting.” Using your power also requires accepting the (potentially unwanted) consequences of a decision. Regardless of how you feel about it, dealing effectively with complaints that fall into the center of your Circle of Control requires deciding and acting.

Announce Intent and Manage Up

A little further out, as you start to approach the Circle of Influence, are complaints that you can address, where you only sort of own the decision. These are cases where the implementation is entirely on you or your team, but whether or not you have the authority to make the decision is fuzzy. You might need someone else’s buy-in or consent. Here, effective managers announce their intent and manage up.

An engineering manager I worked with managed software engineers on three different product development teams – Teams A, B, and C. The director he reported to asked this manager to move a very senior engineer from Team A to Team B. This engineer was an expert with a new tool that Team B needed for their project. That project, the manager discovered, was connected to one of the key initiatives his boss was expected to deliver. The manager had agreed to reassign the engineer with the understanding that the engineer would teach the people in Team B to use the tool themselves – rather than doing all the work that relied on the tool. That seemed to have been successful, and Team B was making good progress on their project.

A few months later, Team C started a new project that also needed the new tool. They complained to the engineering manager about problems with it. They wanted the same senior engineer to join their team and teach them how to use it. Now, team assignments were technically the manager’s decision. At the same time, making this change without involving his director wasn’t the wisest idea. This sat on the line between Control and Influence for this manager.

The engineering manager was tempted to ask the director’s permission to move the engineer to Team C. Instead, he told his boss what he intended to do and why. First, he explained his plan and how it wouldn’t put Team B’s schedule at risk. Next, he explained how he would respond if something unexpected that affected Team B did come up. Finally, he showed how Team C’s new project supported the director’s initiative, further demonstrating his understanding of the situation. In short, he engaged in rigorous thinking about the situation and informed his boss what he intended to do, ensuring his plan aligned with his boss’s success. After all, managing up is about partnership.

Two important things happened. First, the director was impressed by how the manager had shown ownership of the situation, rather than just pointing out a problem or asking permission. Second, the director said the original idea to put the senior engineer on Team B came from the CTO. In the CTO’s next weekly staff meeting, the director communicated the intent to move the engineer to Team C, using the same rationale the engineering manager had provided. The CTO nodded and said, “Makes sense. Do it.” The next day, they did.

Use Your Authority to Manage (Some) Complaints

In both approaches, addressing complaints requires taking action, either directly or indirectly. The key to managing these types of complaints is embracing your decision-making authority. Even when you need to engage others, a solution arises from your willingness to drive things forward.

Unfortunately, there are other situations where using your authority isn’t sufficient. We’ll explore those – and other practical approaches – in Part Two.