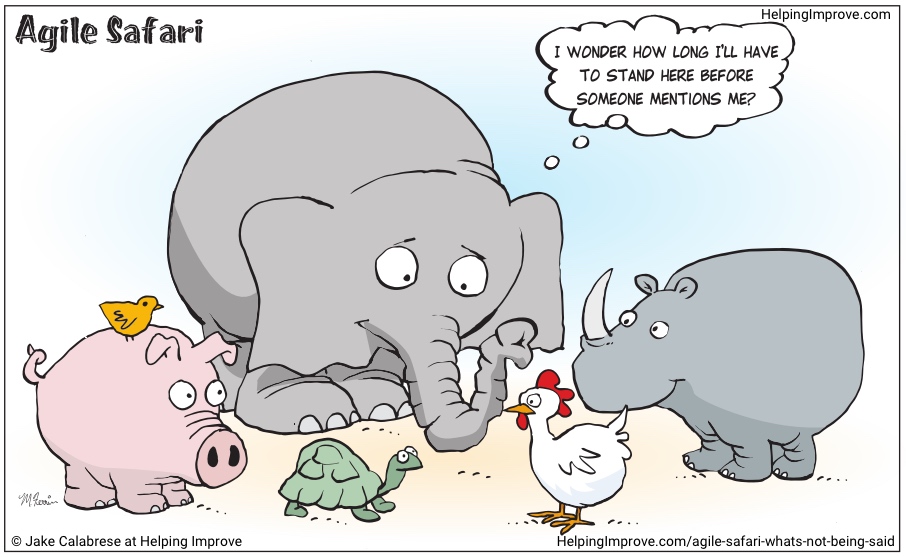

Open Space Conferences, Events, and Workshops are one of my favorites ways to learn. Many people have never had the opportunity to experience an Open Space Event or even know what it is. I hope you can learn more about Open Space and even attend an event and experience the amazingness!

Imagine walking into a large conference or event room with 100 or 1500 people. You look around the room and know only a few people. You see a blank wall with time slots and room names on it.

Two facilitators kick the event off. They explain a light structure for success, a few core principles, and create a fun energy in this large room. They invite anyone in the room (including you) to propose a session on a topic that is of value to them. Simply step up to the microphone and propose a session. You can’t imagine proposing a session, but plenty of other people are. The person sitting next to you stands up and heads over to the mic to propose a session. You notice that blank wall of time slots filling up with a variety of session topics! Next thing you know, you are in line proposing a session! Wait – what happened! As the time to propose sessions is up, there is now a large wall (or marketplace) of sessions to choose from. You decide on a session to attend in the 1st time slot and head over to that session ready to learn and contribute! And still a bit surprised that this worked!

Two facilitators kick the event off. They explain a light structure for success, a few core principles, and create a fun energy in this large room. They invite anyone in the room (including you) to propose a session on a topic that is of value to them. Simply step up to the microphone and propose a session. You can’t imagine proposing a session, but plenty of other people are. The person sitting next to you stands up and heads over to the mic to propose a session. You notice that blank wall of time slots filling up with a variety of session topics! Next thing you know, you are in line proposing a session! Wait – what happened! As the time to propose sessions is up, there is now a large wall (or marketplace) of sessions to choose from. You decide on a session to attend in the 1st time slot and head over to that session ready to learn and contribute! And still a bit surprised that this worked!